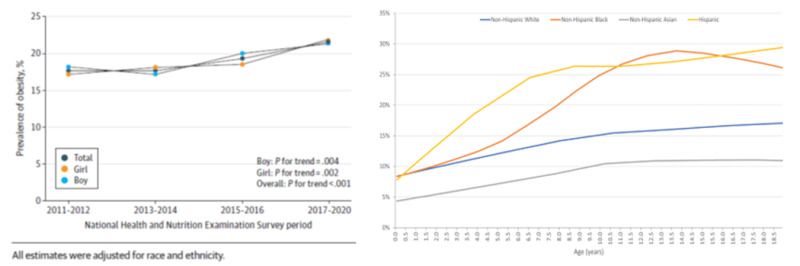

Despite years of public health campaigns encouraging children to “reduce intake and increase activity,” global rates of childhood obesity continue to escalate. In the U.S., nearly 20% of children and teens aged 2–19 years are classified as obese, with even higher prevalence among those from low-income or minority communities. Although caloric balance is a fundamental concept in weight management, reducing obesity to a question of willpower overlooks the intricate physiological, psychological, and environmental influences that lead to excessive weight in children.

New research endorses the perspective of obesity as a chronic, relapsing neuroendocrine disorder rather than merely a lifestyle choice failure. Children affected by obesity frequently display dysregulation of hormones that govern appetite, such as leptin, ghrelin, and insulin. For instance, leptin resistance—a situation where the brain fails to react to satiety indicators—can lead to heightened food consumption even when energy reserves are sufficient.

Additionally, persistent inflammation and modified hypothalamic signaling are significant factors in the homeostatic disruptions noted in pediatric obesity. These biological challenges are not corrected simply through self-control or calorie reduction, explaining why conventional recommendations often fall short.

The roots of obesity frequently start before birth. Epigenetic changes resulting from maternal obesity, gestational diabetes, or inadequate prenatal nutrition may predispose children to increased fat accumulation and metabolic issues. Furthermore, polygenic risk assessments reveal that numerous genetic variations affect body mass index (BMI), appetite control, and energy usage. Although the environment has a modifying effect, many children possess a hereditary propensity to gain weight under standard contemporary circumstances.

Restrictive dietary practices in children can lead to unforeseen repercussions, including stunted growth and development due to nutrient insufficiencies, heightened risk of eating disorders, and metabolic adaptations, where the body conserves energy, complicating future weight loss efforts. Evidence indicates that a significant number of children who pursue intentional weight reduction ultimately regain the weight—often coupled with additional fat and diminished muscle mass. This cycle of weight fluctuation is associated with deteriorating cardiometabolic health over time.

Today’s children are exposed to obesogenic surroundings: areas with scant access to safe play spaces, limited availability of fresh fruits and vegetables, and intense marketing of ultra-processed products. School lunch programs, societal norms surrounding screen time, and economic instability all foster a high-calorie, low-nutrient lifestyle. Even sleep deprivation, now prevalent among teens, correlates with heightened hunger and insulin resistance. These structural factors driving obesity lie beyond the influence of individual behavioral change. Expecting a child to manage their behavior under such circumstances—particularly in the absence of systemic support—is impractical and often unjust.

Treating obesity in children necessitates a comprehensive strategy: medical evaluations for metabolic, endocrine, or genetic factors; behavioral therapies, such as family-oriented counseling and emotional management; nutritional guidance that endorses balanced, non-restrictive eating habits; and environmental changes, including enhancements to school meal programs or zoning laws to curb fast food presence. Pharmacological treatments and metabolic surgery, once restricted to adults, are increasingly being considered for adolescents with severe obesity and related health issues—underscoring the urgency for tailored, evidence-based care.

The simplistic “eat less, move more” narrative fails to recognize the complexities surrounding pediatric obesity as a multifaceted condition. Interventions should be founded on biological, psychological, and environmental insights—not on assigning blame. As our comprehension of obesity progresses, so too must our methodologies for supporting children’s well-being—not just weight reduction.

Callia Georgoulis is a health writer.