Title: The Progression of Medicine: Technology, Economics, and the Decline of Continuity in Patient Care

By Gene Uzawa Dorio, MD

At the outset of my medical journey, tools like CT scans and MRIs, which we now deem fundamental, were nonexistent. Medicine was intrinsically more intimate, depending on clinical discernment cultivated through time spent with patients rather than sophisticated imaging or electronic records. Yet, over the ensuing decades, the healthcare landscape has been transformed at an astonishing pace—primarily propelled by technological advancements and economic factors.

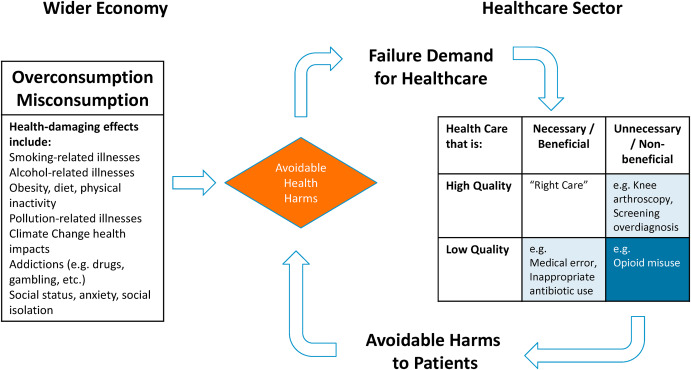

Scientific progress—including the incorporation of computers and digital communication—has enhanced diagnostic precision and streamlined interactions, but a concurrent trend has subtly altered the physician-patient dynamic. This change, driven by profit-oriented entities like insurance companies and hospital managers, has resulted in a concerning decline in the continuity of patient care and physician independence.

The Surge of Advanced Technology in Medicine

CT scans and MRIs represent a crucial advancement in medical diagnostics. These tools empower physicians to visualize the body’s inner workings with unmatched accuracy, often identifying the root causes of symptoms much sooner than earlier techniques permitted. Furthermore, electronic health records (EHRs) and patient portals facilitate smooth information exchange between providers, irrespective of geographical boundaries. This digital transformation has, in theory, simplified the tracking of patients’ progress and ensured alignment in treatment strategies.

Additionally, the emergence of telemedicine and mobile communication continues to close the gap between outpatient visits and inpatient admissions. Even from home, physicians can oversee and modify treatment—a capability that would have seemed impossible just a few decades ago.

Nonetheless, this enhanced capability for care has not resulted in improved patient outcomes universally, largely due to the fragmentation of the healthcare system under economic strains.

From Private Practice to Hospitalist Transfers

For approximately forty years, I have practiced internal medicine in a private setting, serving not only as a physician but also as a small business proprietor. In the conventional model, private practice physicians maintained a continuous relationship with their patients—seeing them in the office and following them into the hospital when necessary. This approach to practicing medicine allowed us to comprehend the patient holistically, factoring in family dynamics and social complexities, thereby making critical decisions, including those regarding end-of-life care, more informed and empathetic.

However, financial administrators perceived this model as ineffective. They regarded the juggling of hospital rounds and office hours as an administrative challenge rather than evidence of a well-rounded physician. Collaborating with insurance companies, hospital administrators developed a new class of physician: the hospitalist.

Hospitalists are board-certified and capable practitioners, often with a focus on internal medicine or family practice. However, most are directly employed by hospitals or affiliated group practices, making them susceptible to economic pressures that extend beyond patient care. With productivity metrics closely monitoring their every action—from lab orders to lengths of stay and specialist consultations—hospitalists often find themselves balancing patient interests with institutional financial viability. This reality considerably hampers their ability to advocate independently for personalized care.

Continuity of Care: A Diminished Skill

The division of care between office-based physicians and hospitalists has compromised a fundamental element of high-quality healthcare: continuity. Patient discharges now heavily depend on hand-offs that may lack the depth and understanding of the patient’s overall health narrative. Despite digital systems intended to facilitate transitions, essential information frequently gets lost—either due to system constraints or unfamiliarity between physician and patient.

For example, returning patients often struggle to recall their admitting diagnosis or the post-discharge care that is necessary. Physicians in private practices, excluded from the inpatient care continuum, find themselves attempting to solve clinical mysteries without complete information—a circumstance that raises the likelihood of hospital readmissions.

The Limitations of Corporate Medicine

Perhaps most concerning is the encroaching authority that hospital administrators have solidified over clinical decision-making. Officially, hospitals are not permitted to practice medicine—a regulation stemming from the premise that clinical choices should remain in the hands of skilled physicians, not business leaders. Nevertheless, through contract manipulation, performance assessments, and restrictive employment conditions, administrators have effectively seized control over the delivery of care.

Young hospitalists, frequently burdened by student debt and family obligations, are particularly susceptible to these coercive pressures. Challenging institutional norms or voicing objections could jeopardize their contracts and professional stability, thereby constraining their ability to fully advocate for patients.

Concurrently, physicians in independent or small-group practices find themselves increasingly marginalized within hospital systems. In certain locations, private doctors are entirely prohibited from seeing their patients in hospitals, compelled to rely on digital communication with hospital personnel to offer input on care. Although this provides a degree of continuity, it does not substitute for the value of enduring physician-patient relationships and the subtle, often non-verbal communications that develop through years of direct interaction.

A System in Conflict: Profit vs. People

Ultimately, what has come to fruition is a healthcare system at odds with its mission. On one hand, technological and medical advancements have enabled the implementation of more accurate, rapid, and focused interventions.