Title: The Quiet Rise of MASH: Understanding Why Fatty Liver Disease Is Increasing Among Young Adults

By Anuj Vikrant Sharma, MD

In recent times, an unforeseen trend has started to reveal itself within the field of digestive and metabolic health. A growing number of seemingly healthy individuals in their 20s and 30s—many of whom drink moderately and maintain a “normal” weight—are receiving diagnoses of a progressive variant of fatty liver disease. Once primarily linked to middle-aged individuals battling obesity or diabetes, this ailment is now surpassing some of those conventional categories, impacting a fresh, younger population.

This condition is currently referred to as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis, or MASH, and it is quietly emerging as a significant public health issue.

Grasping MASH

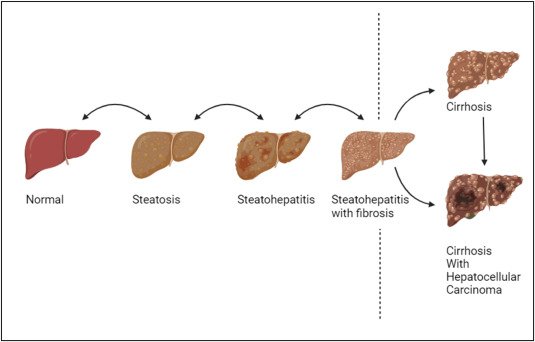

MASH represents a more serious variant of fatty liver disease, which can range from simple fat accumulation in the liver (steatosis) to inflammation and eventual scarring (fibrosis). If not managed properly, it may advance to cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer.

One particularly concerning aspect of MASH is its unnoticeable advancement. In its initial phases, MASH typically shows no symptoms. Routine blood tests might indicate only minor variations—or none at all. Imaging may not occur unless there are compelling clinical reasons. By the time symptoms emerge, considerable damage might have already occurred.

The Hidden Influence of the Gut-Liver Axis

If an individual is not obese and does not consume excessive alcohol, how do they develop liver disease?

A crucial yet often ignored answer resides within the gut microbiome—the extensive community of microbes residing in our digestive system. The gut and liver are interconnected through the gut-liver axis. When the microbiome is functioning well, it sustains a balanced immune and metabolic landscape. However, when this system becomes unbalanced—a state known as dysbiosis—the repercussions can spread throughout the system, including the liver.

Dysbiosis boosts intestinal permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut,” which permits inflammatory substances such as endotoxins and undigested food fragments to enter the bloodstream. These detrimental elements make their way directly to the liver via the portal vein. Upon arrival, they trigger inflammation and fat buildup, laying the groundwork for MASH.

The Dietary Aspect: Beyond Calories

Dysbiosis is largely fueled by diet. The contemporary Western eating patterns, abundant in ultra-processed foods, added sugars, fats, and deficient in fiber, set the gut environment up for inflammation. Typical food additives—such as emulsifiers, artificial sweeteners, and preservatives—can also disrupt microbiome diversity.

Importantly, this renders MASH not merely a condition of caloric surplus but also one of dietary quality. This sheds light on why slim or active individuals may succumb to fatty liver disease—they might seem outwardly healthy, but their dietary choices could still harm the gut and liver due to poor microbial health.

The Urgent Need for Action

The escalation of MASH among younger adults is a warning signal. Unlike many chronic conditions that require years to manifest, MASH can develop quickly. Within a span of 10 to 20 years from the onset, an individual might confront cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer), or may even require a liver transplant. Additionally, those affected face a heightened risk for other serious illnesses, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Despite these dangers, routine screening for fatty liver disease is not yet standard practice among young or lean patients. Many healthcare providers, as well as the general populace, continue to regard “fatty liver” as a harmless incidental finding, overlooking the critical opportunity for early intervention.

The Potential for Reversal

Perhaps the most encouraging feature of this condition is its potential for modification. The liver possesses an extraordinary capacity to recover—provided the sources of metabolic and inflammatory strain are eliminated early on.

The priority is to act before irreversible scarring or cirrhosis occurs, which necessitates that both healthcare providers and patients adopt a proactive and comprehensive approach early in the course of the disease.

A Gut-Centric Approach

To tackle the escalating issue of MASH—especially among younger demographics—we require a multi-faceted strategy involving prevention, early detection, and dietary reform, with a focus on the gut microbiome.

Here are practical steps ahead:

1. Incorporate Liver Health Screenings for High-Risk Individuals:

Primary care appointments should include liver enzyme evaluations and liver imaging—even for young adults—if they exhibit signs of metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, or adhere to a processed diet.

2. Prioritize Food Quality Over Quantity:

Nutritional guidance should shift from mere calorie counting to emphasizing fiber-rich foods such as vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and fermented products. These foster a diverse and healthy microbiome while lessening hepatic inflammation.

3. Raise Awareness About the Gut-Liver Connection:

It is vital to inform both patients and providers that gut health has a direct impact on liver function—encouraging lifestyle choices that benefit both.

4. Support Research in Microbiome-Based Treatments:

More investigation is necessary into