In the late 1970s, Akira Endo, a Japanese biochemist, identified a substance derived from fungus that inhibited HMG-CoA reductase, the enzyme that produces cholesterol. This finding was first met with academic interest, as its capacity to prevent heart attacks was unverified—it simply lowered a laboratory measurement. This substance transformed into lovastatin, and in 1987, Merck launched it into the market without confirmed results but with a hopeful mechanism and a theory pending verification. The pivotal 4S trial in 1994 demonstrated that statins could save lives, reinforcing their narrative.

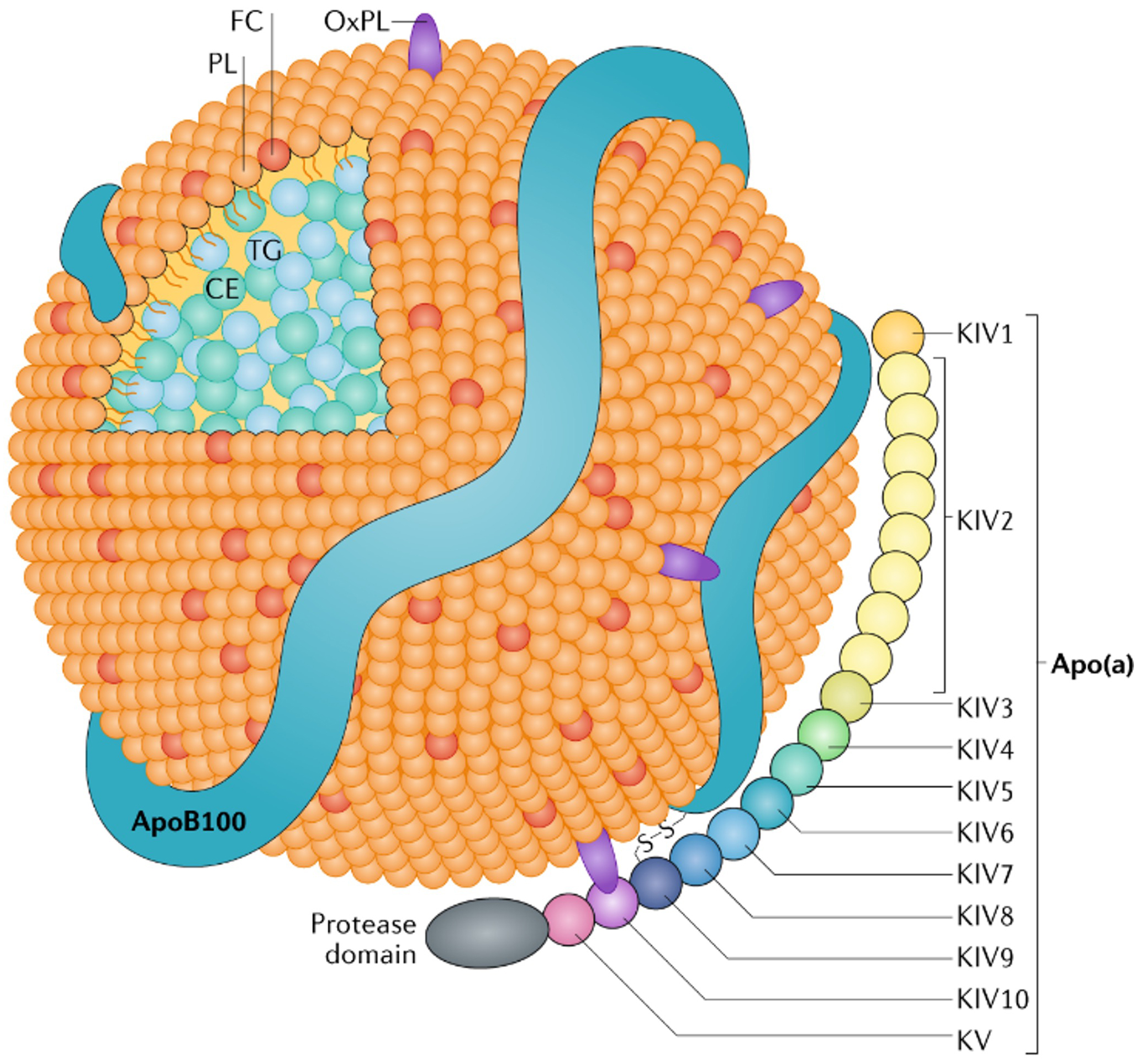

Statins represented a significant shift, altering therapeutic emphasis from treating disease to managing risk, and focusing on surrogate markers instead of the illness itself. Presently, a comparable approach is directed at Lp(a), an LDL-like particle linked to heart disease and aortic stenosis. These particles are hereditary, difficult to quantify, and largely immune to lifestyle modifications, making them an attractive focus for innovative biotech solutions.

Biotech firms are creating treatments like pelacarsen, olpasiran, and SLN360 to lower Lp(a) levels. While capable of diminishing Lp(a) by up to 98%, these therapies have not yet demonstrated a reduction in cardiovascular incidents. Nonetheless, the foundation for their implementation is already being established through advisory boards, educational programs, and pharmaceutical-funded research. The narrative is being formed even before effectiveness is established.

This situation mirrors the Sackler family’s launch of OxyContin, where a disease framework was constructed around inadequately managed pain using a claim from a 1980 NEJM letter lacking supporting data. Likewise, Lp(a) is being approached as a target without proven therapeutic advantage. It may function as a marker rather than a modifiable risk factor, akin to previous failures with CETP inhibitors.

The historical lesson is that waiting for definitive results is essential before accepting new therapies. As the narrative concerning Lp(a) treatments evolves, it prompts critical inquiries about proof and trust in pharmaceutical innovations. The potential danger of unnecessary treatment highlights the necessity of data-driven choices in healthcare.