I recall a patient in her early sixties who visited our clinic experiencing mild memory issues. She resided alone in a rural county, depended on Medicaid, and had been shuffled between social services and various primary care providers for over a year. Imaging had never been ordered, and there were no neurologists in the vicinity. By the time Alzheimer’s disease was considered, her opportunity for early intervention had already passed.

Medicare has recently broadened its coverage for amyloid PET scans, providing more patients with a route to earlier diagnosis. However, for the millions covered by Medicaid, particularly those at the highest risk, access to even fundamental diagnostic tools remains constrained. Blood-based biomarker tests are now clinically validated and increasingly accessible, yet most Medicaid programs have failed to adjust their coverage to reflect this change. This gap in policy hinders diagnosis and limits treatment options.

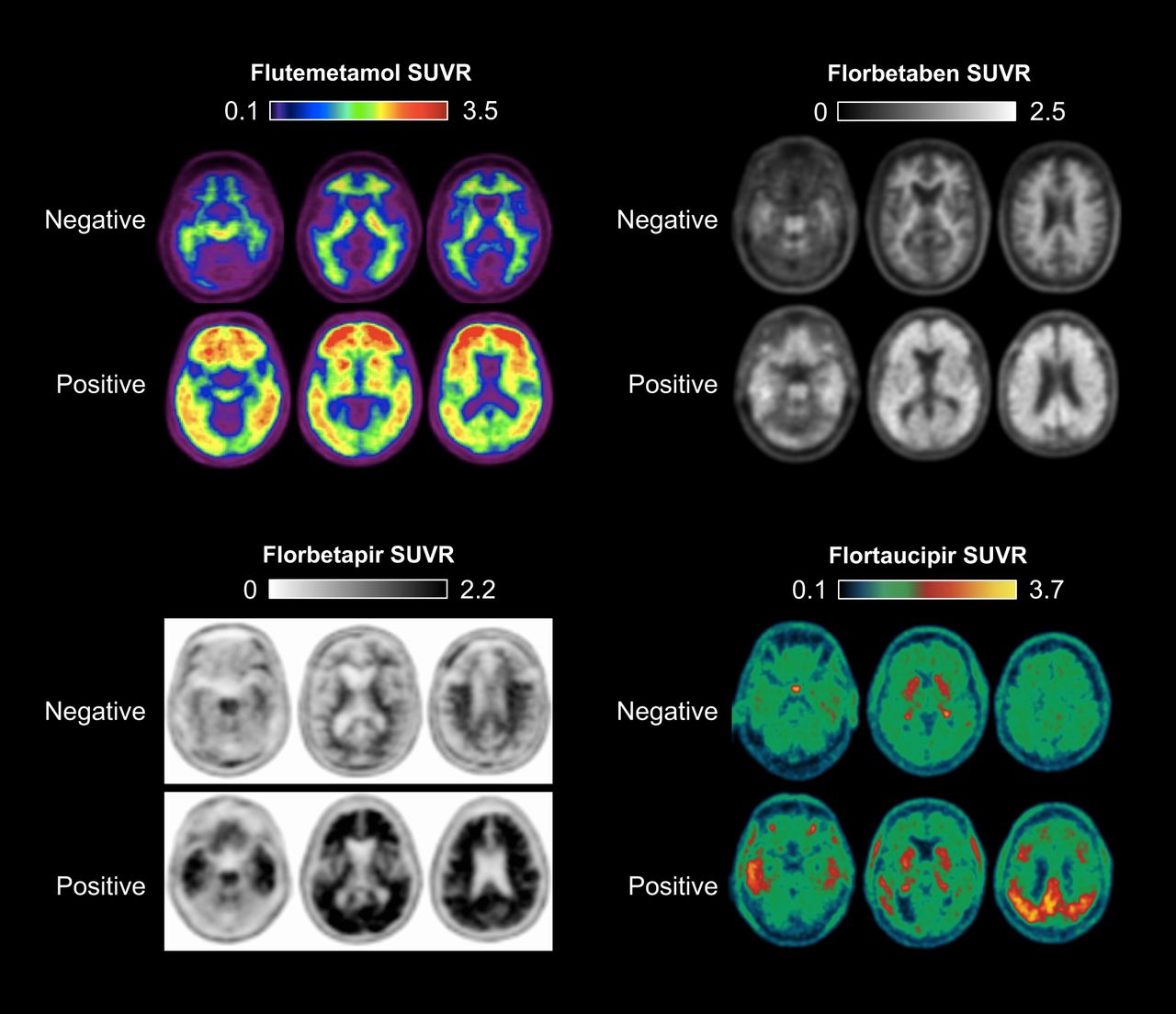

Plasma biomarkers such as the Aβ42/40 ratio, phosphorylated tau (p-tau181), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and neurofilament light chain (NfL) can identify early developments in Alzheimer’s disease with notable accuracy. These tests are less invasive than spinal fluid analysis, more cost-effective than PET imaging, and simpler to implement in primary care environments. Their significance has grown with the introduction of new disease-modifying therapies like lecanemab and donanemab, both of which necessitate biomarker verification before administration.

In May 2025, the FDA approved the first Alzheimer’s blood test through the substantial equivalence pathway, acknowledging it as comparable to current diagnostic methods. Despite this achievement, the majority of Medicaid programs have not included these tests in their coverage schemes. A review of all 51 state Medicaid programs indicated that merely 18 reference Alzheimer’s blood tests in their public coverage documents. Less than half provide billing codes, and very few recognize the access challenges confronted by medically underserved patients. Meanwhile, PET scans and spinal fluid assessments are still covered in most states, although they tend to be pricier and less accessible, particularly in rural areas.

This disparity perpetuates long-standing inequalities in care. Black and Hispanic adults are more likely to rely on Medicaid, more prone to develop Alzheimer’s, and more susceptible to delayed diagnosis. Excluding lower-cost, clinically appropriate diagnostics from coverage exacerbates these inequities.

Some states have begun to take action. In 2024, Florida enacted legislation mandating Medicaid to cover Alzheimer’s blood tests. While the implementation will differ across care environments, the clinical justification is evident. However, in the absence of federal direction, most states have not progressed. Access to diagnostics now relies less on medical necessity and more on geographic location.

To bridge the divide, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services should provide formal guidance endorsing coverage for FDA-approved blood-based diagnostics. This would enable states to create consistent billing practices and implementation approaches that prioritize access from the outset rather than waiting until disparities arise.

We already possess the means to detect Alzheimer’s earlier, more affordably, and in a manner that alleviates the burden on both patients and providers. The true barrier is not technology, but policy. Clinicians and caregivers continue to witness the consequences of delayed diagnosis, particularly in communities with limited access to specialized care. Medicaid programs have a chance to tackle this issue head-on. Patients should not be denied prompt diagnosis merely because their insurance hasn’t evolved with scientific advancements.

*Amanda Matter is a student pursuing a doctorate in pharmacy.*