“My PSA returned at 6.2 — does that indicate I have cancer?”

This is one of the most prevalent and emotionally charged inquiries I encounter in the clinic. The prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test, once hailed as a pivotal advancement in early cancer detection, has evolved into a double-edged sword. For numerous men, a mildly raised PSA level is enough to incite panic — and for certain physicians, sufficient to initiate a biopsy.

But here’s the reality: PSA levels do not equate to a diagnosis. They represent only one aspect of a significantly broader clinical picture. When assessed in isolation, devoid of context or nuance, they can result in unwarranted anxiety, procedures, and even overtreatment.

As urologists, we need to improve, not by discarding PSA testing, but by reevaluating how we employ it. Because one single number should never dictate a man’s cancer risk.

What PSA levels truly signify – and do not

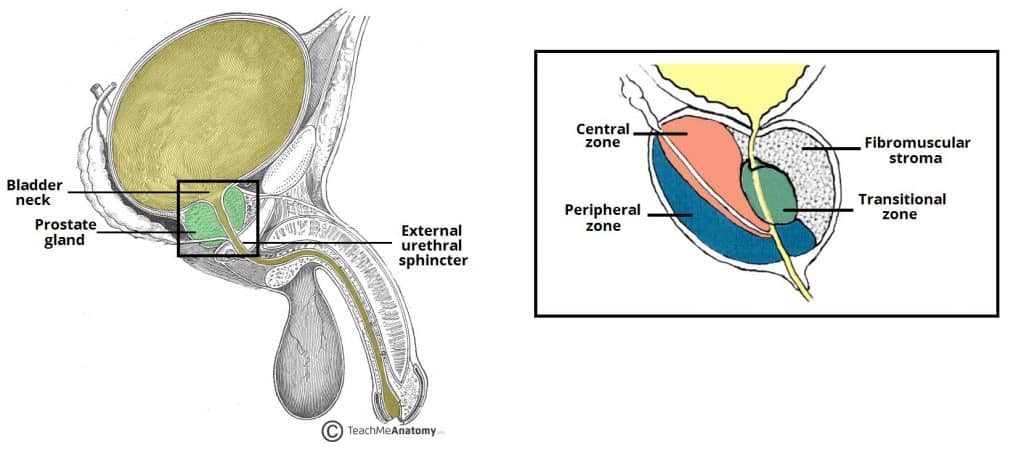

PSA, or prostate-specific antigen, is a protein secreted by both normal and cancerous cells in the prostate. A small quantity naturally circulates in the bloodstream, with the PSA test quantifying its concentration.

While a heightened PSA level may heighten worries regarding prostate cancer, it’s crucial to comprehend that PSA is not cancer-specific. In fact, numerous non-cancerous conditions can elevate PSA levels, including:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) — a common, non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate

- Prostatitis — inflammation or infection of the prostate

- Recent ejaculation, vigorous exercise, or even a digital rectal exam before the blood draw

PSA levels naturally rise with age and prostate volume, meaning what’s considered “elevated” in one patient might be entirely normal in another.

This is where confusion frequently arises, because while the PSA test is sensitive to prostate activity, it lacks the specificity to indicate why the number is elevated.

The issue with depending on a single cutoff

For years, a PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL was broadly accepted as the benchmark for concern. If you surpassed that threshold, you were often referred for a biopsy. If you were below it, you were reassured everything was fine. However, real-world data and decades of clinical experience have revealed that this binary approach is grossly flawed.

Prostate cancer can and does develop in men with PSA levels below 4.0. Simultaneously, many men with PSA levels exceeding 4.0 do not have cancer whatsoever. Indeed, substantial studies have shown that relying on a single cutoff point can lead to both overlooked cancers and unwarranted procedures.

The reality is that PSA levels exist across a spectrum. A one-size-fits-all threshold oversimplifies a biologically intricate disease, and it risks causing more harm than benefit.

That’s why contemporary urology is transitioning away from the strict cutoff model. Rather than asking “Is it above 4?”, we should be inquiring “What does this PSA represent in the context of this individual man?”

Overdiagnosis and overtreatment: Genuine harms from misinterpretation

One of the most significant and often disregarded repercussions of misinterpreting PSA levels is overdiagnosis. This refers to the identification of prostate cancers that are so slow-growing or biologically inactive that they would never have caused harm during a man’s lifetime.

However, once a man hears the word “cancer,” even if it’s low-risk, it often triggers a cascade: biopsy, anxiety, surgery, radiation, and side effects that may never have been necessary. These treatments, while life-saving in the appropriate context, come with legitimate risks, including erectile dysfunction, urinary incontinence, and psychological distress.

This is not a rare situation. Research estimates that a significant proportion of men diagnosed through routine PSA screening undergo unnecessary treatment for cancers that might never have advanced.

The aim is not to disregard prostate cancer; it’s to address the right cancers in the right patients at the right time. This begins with realizing that an elevated PSA level does not always necessitate immediate action, and sometimes, doing less is indeed better.

More intelligent ways to utilize PSA: Context is crucial

Rather than reacting to a single PSA level in isolation, clinicians today are advised to undertake a broader risk assessment. PSA should be interpreted not as an isolated figure, but alongside a variety of patient-specific factors.

Among the most useful tools we now possess are: