As a reproductive endocrinologist, I encounter numerous patients who come to my practice carrying silent stories of loss—sometimes a loss of hope, other times a loss of time. However, annually, there’s a specific group of men who present with a remarkably similar background.

They hail from varied countries. Many were raised in areas where the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine was either unavailable or inconsistently provided. They experienced mumps during childhood, recovered, and moved on without a second thought.

Fast-forward 15 or 20 years, and they find themselves as adults wishing to become fathers. Only at this point do they realize that their childhood mumps infection has left a lasting impact: azoospermia—the total absence of sperm in their semen.

It is for them, and those who may be affected, that I am composing this article. Even though we don’t discuss it often anymore due to vaccinations, mumps orchitis continues to be a cause of acquired male infertility around the globe.

What is mumps orchitis?

Mumps orchitis is the inflammation of one or both testicles caused by the mumps virus, which is a single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Paramyxoviridae family. It typically manifests 4–10 days after the characteristic swelling of the parotid glands, though in roughly 10 percent of cases, it occurs in isolation without parotitis.

This condition primarily targets post-pubertal males, with the highest rates between the ages of 15 and 29. Historically, prior to widespread vaccination, 15–30 percent of post-pubertal males with mumps developed orchitis, with 60–70 percent being unilateral and up to 40 percent bilateral.

How does it damage fertility?

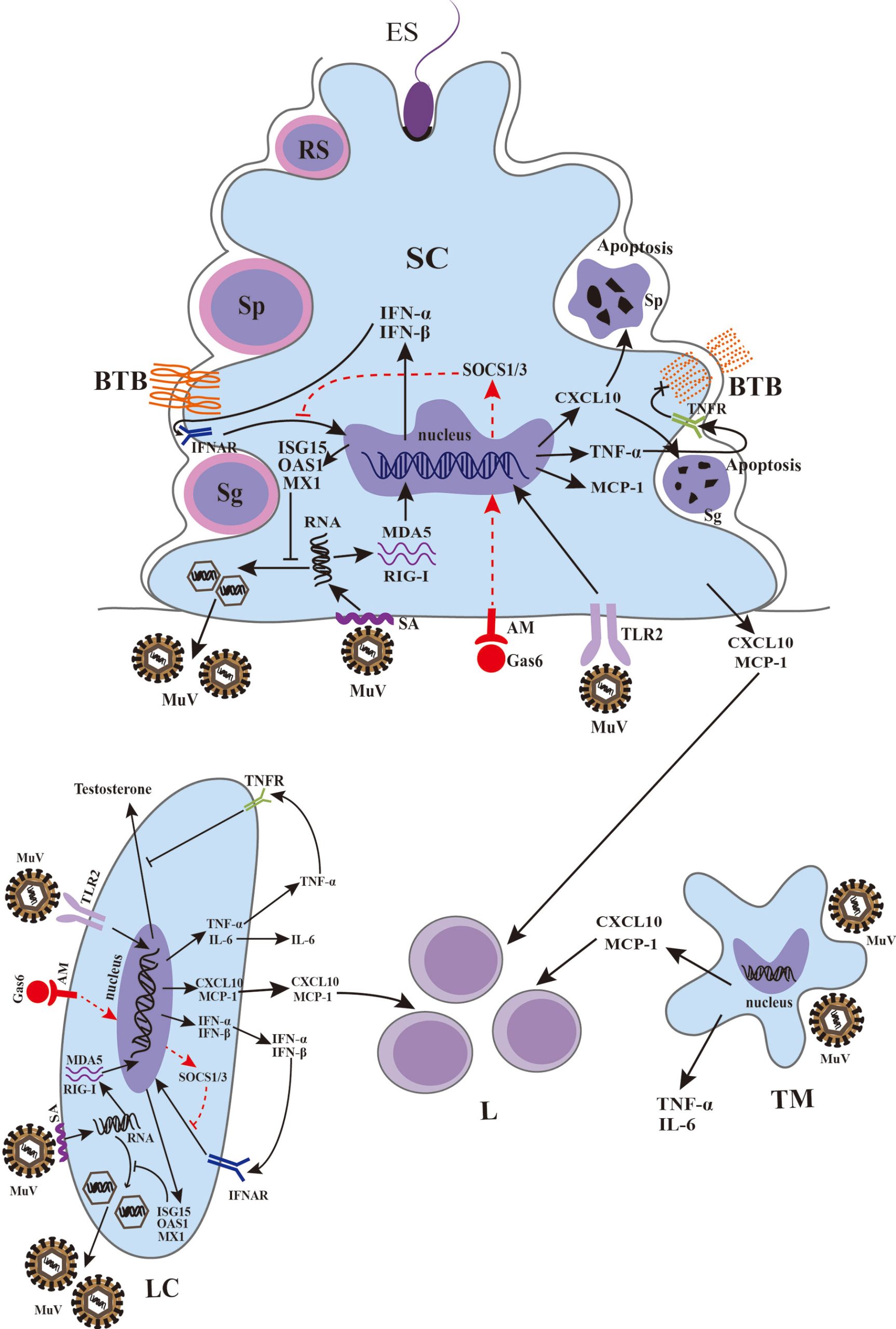

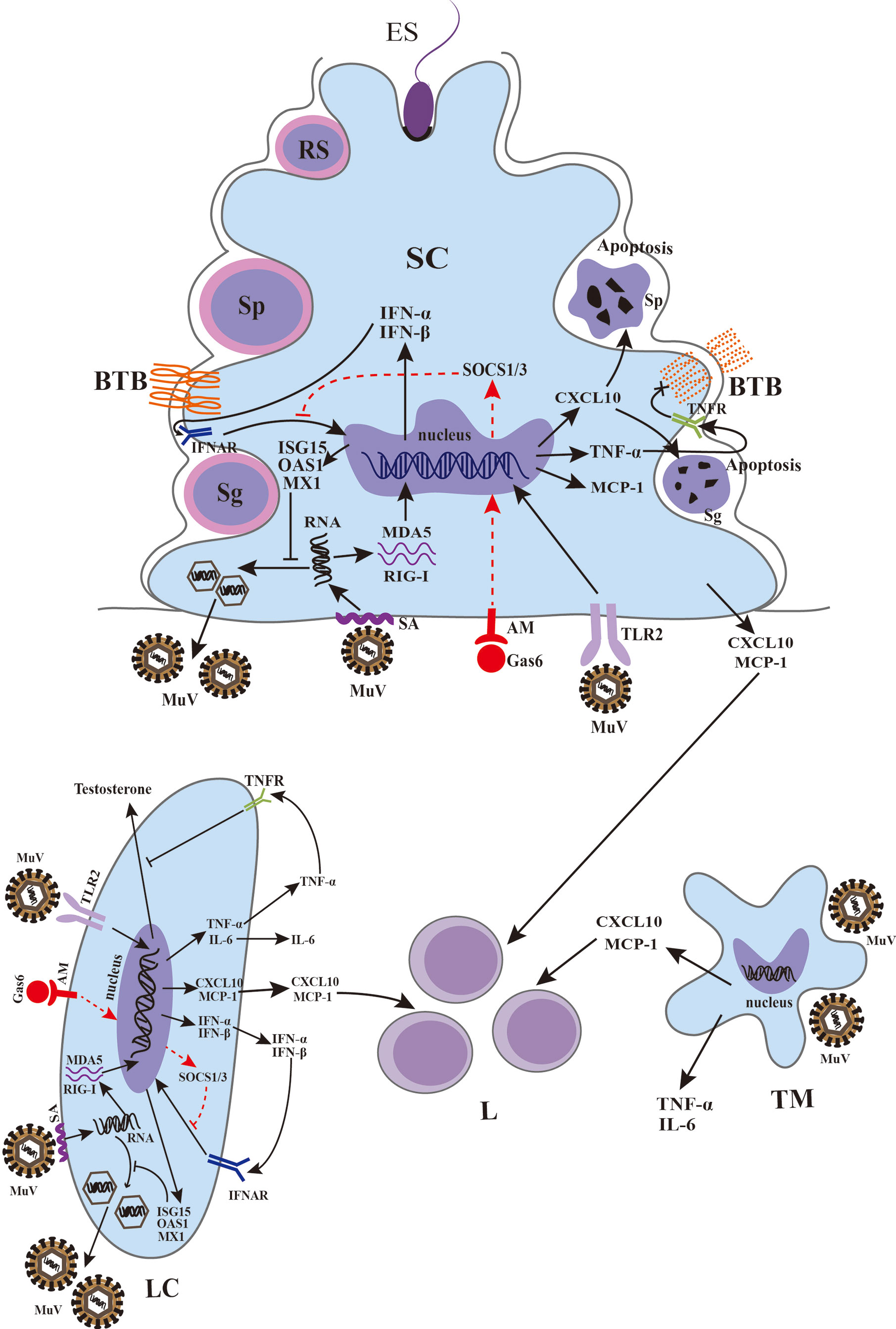

The virus spreads from the respiratory system, enters the bloodstream, and settles in the testicular tissue. Within the testes, it infects the seminiferous tubules and interstitial cells, resulting in:

– Immune-mediated inflammation and swelling

– Increased intra-testicular pressure leading to ischemia and tissue death

– A surge of cytokines that disrupts the blood–testis barrier

– In some bilateral instances, the development of anti-sperm antibodies and autoimmune infertility

This inflammatory process causes irreversible harm to the germinal epithelium that is essential for sperm production. Notably, Leydig cells (which produce testosterone) are relatively unaffected, so testosterone levels often remain normal even when sperm production is compromised.

What are the long-term outcomes?

The extent of fertility impairment is influenced by whether the orchitis is unilateral or bilateral:

– Unilateral orchitis: Generally does not result in sterility but may temporarily or slightly diminish sperm quality.

– Bilateral orchitis: Carries a 30–87 percent likelihood of infertility, often due to severe oligozoospermia or azoospermia.

Testicular atrophy occurs in 30–50 percent of the impacted testes, significantly affecting spermatogenesis.

Treatment and prevention

No antiviral treatment exists. Care is supportive—NSAIDs for pain management, scrotal support, and rest. The real breakthrough is vaccination. Two doses of the MMR vaccine provide 88–95 percent effectiveness.

Sadly, in regions lacking strong vaccination initiatives, boys remain at risk. Many of the patients I see in my practice emerge from areas where mumps was endemic during their childhood. They are often heartbroken to discover that the infection they had at eight quietly influenced their aspirations for family-building later on.

Can assisted reproduction help?

Indeed. For men experiencing azoospermia due to mumps orchitis, assisted reproductive technology can provide a pathway to parenthood.

Sperm retrieval rates using micro-dissection testicular sperm extraction are impressively high—75–85 percent, significantly better than idiopathic non-obstructive azoospermia.

After sperm is harvested, intracytoplasmic sperm injection achieves fertilization rates around 78 percent and pregnancy rates approximately 85 percent, with live birth rates near 66 percent, comparable to other infertility causes.

This means that even after bilateral orchitis, many men can still attain biological fatherhood through advanced reproductive methods.

Why am I sharing this?

Because these situations continue to arise.

Every year, I meet a few men who were unaware that their childhood mumps infection could jeopardize their fertility. They often seek my help only after enduring years of unexplained fertility issues. By the time they get to me, they’re grappling not only with azoospermia—they’re dealing with guilt, confusion, and the realization that no one warned them.

I aim to draw attention to this overlooked complication for two reasons:

– To inform doctors and patients in under-vaccinated groups that mumps orchitis is not merely a relic from textbooks—it remains a very real concern.

– To provide hope to those affected. Modern reproductive medicine can frequently retrieve sperm and assist in achieving pregnancy.

The broader context

In many respects, mumps orchitis illustrates a triumph in public health—vaccination has dramatically decreased its occurrence. Yet, it serves as a reminder that vaccines prevent more than just immediate disease.