Alzheimer’s disease acts as a merciless robber, quietly taking away the fundamental aspects of our identities: our memories. It deprives us of treasured experiences, significant connections, and the autonomy that contributes to a lively and gratifying life. Once regarded as a certain outcome of aging or genetics, innovative research is now questioning this viewpoint, proposing that Alzheimer’s may indeed be a kind of metabolic disorder aptly named Type 3 diabetes.

The idea of Alzheimer’s as Type 3 diabetes is not simply conjecture; it represents a transformative shift founded on solid scientific proof. Just as Type 2 diabetes emerges from insulin resistance in the body, Alzheimer’s seems to stem from insulin resistance within the brain. Under normal circumstances, insulin functions like a key, unlocking cells so glucose, the primary energy source for the brain, can enter. However, when insulin resistance occurs, this key no longer works, leaving neurons deprived of energy and initiating a catastrophic chain of damage.

Per the DSM-5, Alzheimer’s disease (classified under major neurocognitive disorder) is marked by notable cognitive decline across areas like complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor abilities, or social cognition. These impairments substantially disrupt independence in daily tasks, necessitating help with activities such as managing finances, medications, or household chores. Initial symptoms generally involve memory problems, particularly trouble recalling recent occurrences, discussions, appointments, and names. This can evolve into deeper cognitive issues including poor judgment, spatial disorientation, language challenges, and significant personality or behavioral changes.

The hippocampus, our brain’s vital memory hub, is rich in insulin receptors. In Alzheimer’s, the malfunction of these receptors is akin to the insulin resistance noted in diabetes. As insulin signaling falters, glucose absorption is compromised, leaving neurons undernourished and at risk. The repercussions are severe: harmful beta-amyloid plaques build up, tau proteins develop damaging tangles, oxidative stress heightens, inflammation swells, and neuronal death results.

People with diabetes face a substantially elevated risk of developing Alzheimer’s. Research from the Mayo Clinic indicates that diabetes can double or even quadruple this risk. This troubling link is further reinforced by the Alzheimer’s Foundation, which emphasizes the significance of effective diabetes control in lowering the risk of Alzheimer’s.

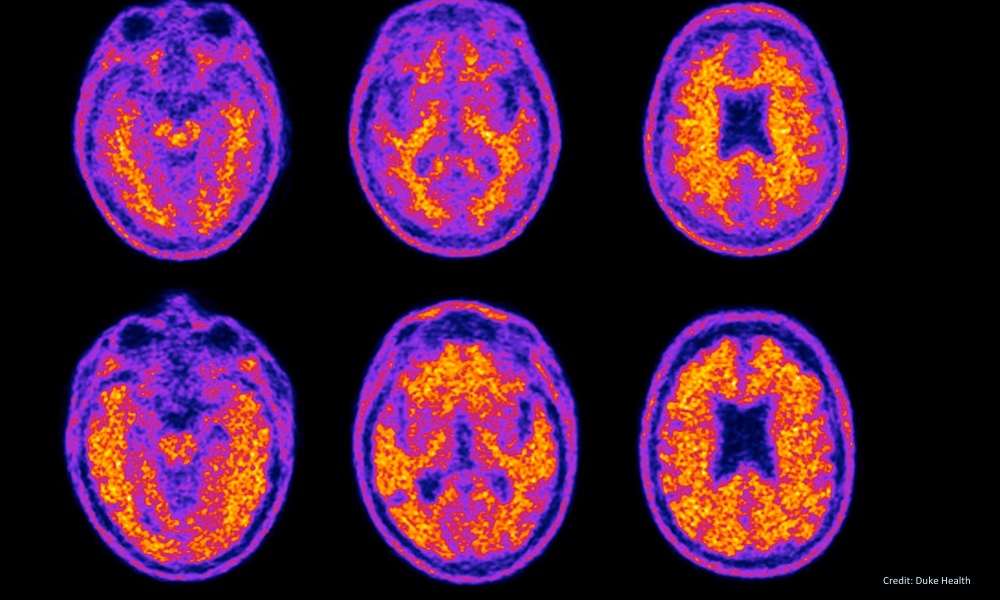

Traditionally, diagnosing Alzheimer’s involved cognitive assessments like the Mini-Mental State Examination and neuroimaging techniques, which usually identify changes only after significant brain damage has occurred. Fortunately, recent advancements bring hope. The FDA has recently approved the PrecivityAD2 test, the first blood test capable of diagnosing Alzheimer’s by analyzing the ratio of amyloid beta 42 to amyloid beta 40 proteins alongside genetic markers like APOE4. When combined with routine diabetes screenings, such as fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1C, Alzheimer’s could soon be detected and managed years prior to the onset of debilitating symptoms.

Picture a visit to your doctor where your cognitive health is assessed along with your cholesterol and blood sugar levels. “Your blood glucose is elevated, your insulin sensitivity is declining, and early indicators of Alzheimer’s are present. We need to take action now, not when your memory fails, but immediately.” This situation is not a far-off fantasy; it is swiftly becoming a reality.

Implementing practical lifestyle changes can significantly lower the risk of Alzheimer’s. Regular physical activity remains unmatched in enhancing insulin sensitivity, preserving neuronal health, and potentially eliminating harmful amyloid plaques. Dietary strategies focusing on antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, polyphenols, and the Mediterranean diet effectively reduce inflammation and bolster insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, mindfulness practices, ensuring restorative sleep, engaging cognitively, and nurturing strong social relationships provide protective advantages against cognitive decline.

Medication options for early intervention are also rapidly increasing. Established treatments like cholinesterase inhibitors (Donepezil, Rivastigmine, Galantamine) and NMDA receptor antagonists (Memantine) offer symptomatic relief and can slow disease progression when started early. Recent research indicates that diabetes medications such as Metformin, GLP-1 receptor agonists (including Liraglutide and Semaglutide), and SGLT-2 inhibitors may also provide cognitive benefits through improved insulin sensitivity and reduced inflammation in brain tissue. Moreover, ongoing clinical trials of monoclonal antibodies targeting beta-amyloid plaques continue to show promise for stopping disease progression.

Natural therapeutic alternatives also contribute. Nutraceuticals like curcumin, known for its anti-inflammatory effects, and omega-3 fatty acids, recognized for their neuroprotective properties, have shown potential in decreasing Alzheimer’s pathology, as comprehensively reviewed in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

Viewing Alzheimer’s from a metabolic standpoint provides us with proactive methods for prevention and early intervention. It transforms our approach and integrates metabolic care directly with cognitive health management.

The message is direct and urgent: Alzheimer’s does not need to be inevitable. It can be prevented, managed, and possibly reversed by recognizing its metabolic foundations. Through collective awareness, advocating for early detection, and prioritizing metabolic health, we can reclaim