Before advocating for the advancement of formal fellowships for physician anesthesiologists to deliberately and systematically object to unnecessary health care, especially unnecessary procedures, it is essential to first examine what is defined as “necessary.” Only after this can we begin to govern what might be deemed “unnecessary.” Can physician anesthesiologists spearhead such academic and practical regulatory initiatives, even amidst potential conflicts of interest that stem from their roles as anesthesia care providers?

This prompts several crucial questions. Is the necessity of any procedure defined by its capacity to safeguard the well-being of the patient, provider, and payer, thereby preventing the first, second, and third victim phenomena? Or is it shaped by economic factors, striving to provide affordable care for patients while maintaining productivity and profitability for providers and payers?

At its core, can anything truly be labeled “unnecessary” unless resources are entirely lacking to conduct even the essential, or are so limited that necessary procedures are postponed, potentially leading to litigation? Even with prospective formal training in conscientious objection, can anesthesiologists effectively challenge proceduralists and their patients on the necessity of interventions, particularly when those procedures are financed by third-party payers, irrespective of value?

Who is to determine that the “unnecessary” hasn’t equipped health care systems to handle the “necessary,” fostering skillsets and infrastructure in expectation of heightened demand? Who can say if certain “unnecessary” procedures are propping up the health care economy, while some “necessary” ones are sidestepped for fear of litigation, with safety becoming a secondary advantage for all involved?

The conundrum is ongoing: Necessity frequently remains subjectively defined, and the equilibrium between tolerating the unnecessary versus protecting the necessary continues to be elusive. Nonetheless, physician anesthesiologists are not without power. They have already reinvented anesthesia care through the safety paradigm. They assertively articulate a contextual “no” when anesthesia environments seem unsafe, thereby safeguarding patients (first victims), providers (second victims), and systems (third victims).

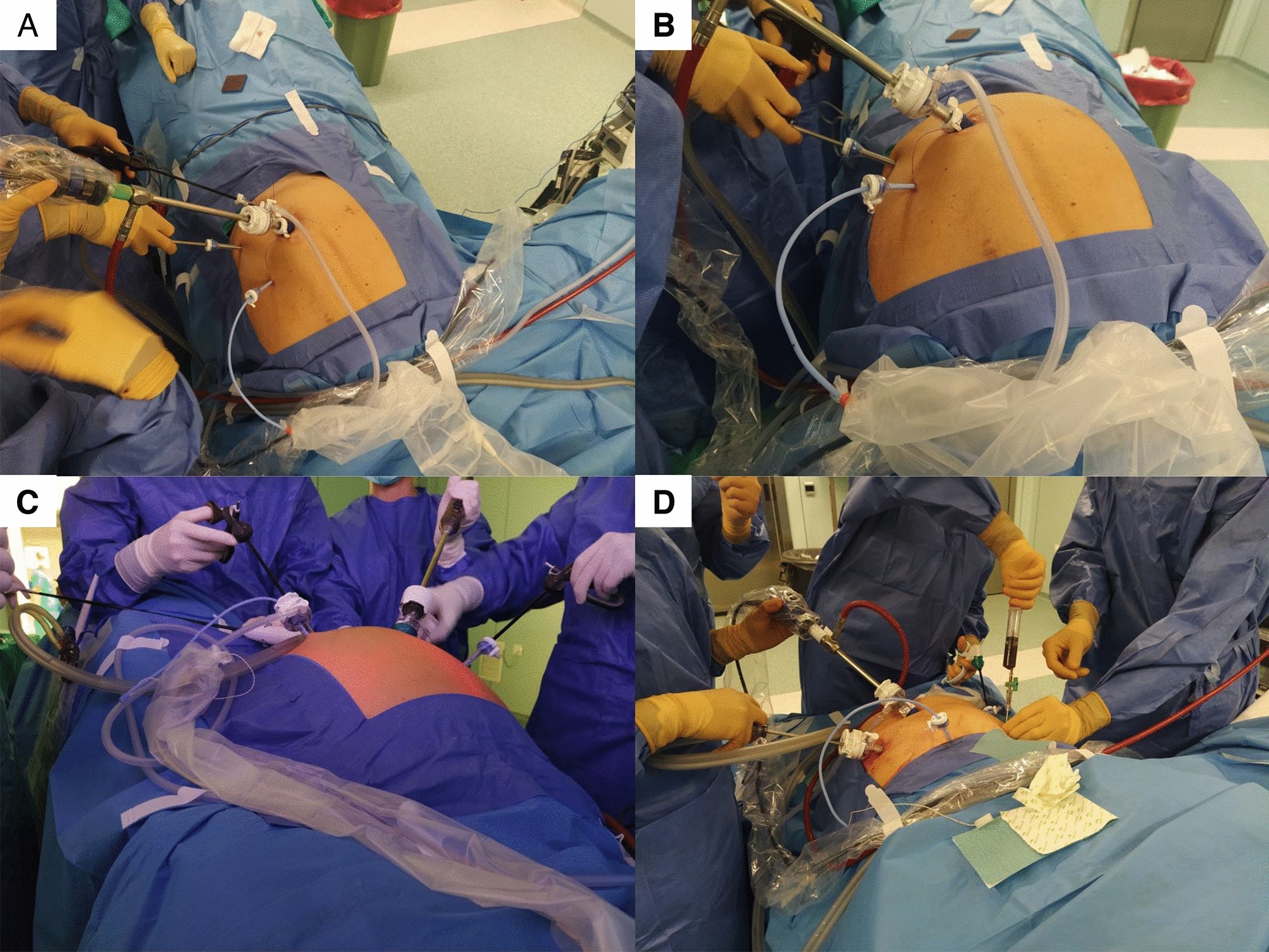

This safety-first method has cultivated unprecedented levels of care. It has even facilitated elective, proactive extracorporeal membrane oxygenation when the need for procedures is evidently justified for patients, providers, and systems alike.

The question now shifts: Should anesthesiologists also commence articulating a clear, contextual “no” to administering anesthesia for procedures that seem unnecessary, even when they can be performed safely? Moreover, if unnecessary procedures are discontinued, would the cost reductions for patients, providers, and systems be sufficient to justify compensating anesthesiologists for their gatekeeping role?

Although anesthesiologists may never obtain authority over pre-authorizations or reimbursement resolutions for unnecessary care, they can enhance their role in curtailing inadvertent facilitation of such procedures. Until formal fellowship training in conscientious objection is realized, anesthesiologists must seek self-education and refine their clinical and academic discernment regarding procedural necessity. Ideally, these evaluations should happen collaboratively with patients, providers, and payers in pre-procedure clinics. The procedure date itself is simply not the right moment or place to evaluate necessity.

If inertia within health care economics thwarts the establishment of such fellowships, anesthesiologists might even contemplate pioneering cash-only anesthesia care. This would empower them to assert a necessary “no” to dubious procedures, particularly when linguistic, cultural, or informational divides between patients, providers, and payers cloud clarity surrounding necessity and consent.

Ironically, cash-only anesthesia care could relieve conscientious anesthesiologists from the ethical burden of enabling unnecessary procedures. This notion is particularly relevant when well-informed, self-aware patients willingly pay out-of-pocket for both anesthesia and their selected, albeit seemingly unnecessary, procedures.

Deepak Gupta is an anesthesiologist.