In July, I authored an article that underscored the importance of end-of-life planning (EOL). Recently, I examined a study concentrating on physicians’ EOL plans for patients suffering from advanced cancer and unspecified-stage Alzheimer’s disease. This research encompassed nations with diverse forms of assisted dying, ranging from the U.S.—where a terminal coma is frequently the sole legal option in numerous states—to Belgium, which permits physician-assisted dying (PAD) and euthanasia. It is crucial to differentiate that PAD is often incorrectly termed as suicide; the genuine objective is not to die but to exercise control over the timing and manner of death.

A terminal coma acts as a palliative intervention for patients whose pain cannot be otherwise managed. In this condition, a patient remains unconscious until death occurs. Euthanasia entails a physician-administered lethal injection that stops breathing, allowing the patient to slip into sleep and ultimately stop breathing.

Numerous U.S. states and other nations provide PAD, where a doctor prescribes an oral medication, like an opioid, that the patient must take themselves. Many who choose this pathway find comfort in this autonomy, with 80% deciding against utilizing the prescription, instead permitting the illness to progress naturally. This creates an equity dilemma for individuals with disabilities and those whose conditions hinder self-administration.

Surprisingly, physicians frequently neglect available technology for more nuanced end-of-life options. For cancer patients, only 0.5% selected CPR, while just 0.2% of Alzheimer’s patients opted for it. Preference for mechanical ventilation was under 1%, and tube feeding was chosen by 3% of cancer patients and 4% of those with Alzheimer’s. It was not specified whether a nasal-gastric or PEG tube was utilized, although the PEG tube is more invasive and susceptible to infection.

In the study, over half of the doctors surveyed regarded euthanasia and PAD as favorable choices. Palliative sedation, typically reserved for uncontrollable pain, was chosen by 59% for cancer and 50% for Alzheimer’s patients.

Decision-making was influenced by external elements such as legal structures, societal standards, workplace beliefs, patient volumes, and medical specialties, in addition to internal values shaped by education, religion, and personal experiences.

In the U.S., the dominant medical ethic focuses on curing or, at the very least, prolonging life—though this perspective is not universally held across the globe. Notably, a physician’s gender or age did not affect their decisions.

Ethical dilemmas emerge in interactions between patients and providers, particularly regarding the autonomy and impact of physicians based on their personal beliefs. The study raised questions about whether these beliefs distorted the information conveyed to patients or if doctors managed to maintain personal and professional boundaries—posing concerns of undue influence.

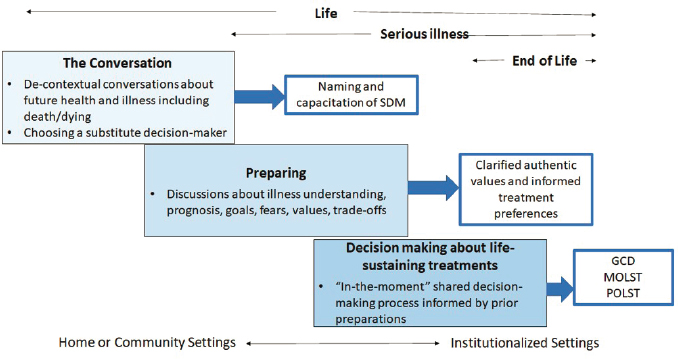

Previous research suggested that physicians might present biased information reflective of their preferences, thereby influencing patient decisions. The authors advocated for discussions early in the process to mitigate coercive pressures on patients. This strategy resembles my technique in disease counseling—offering information accompanied by a disclaimer that choices should reflect individual values, not my own.

Sadly, contemporary healthcare systems do not provide sufficient time for the comprehensive discussions essential for effective EOL planning. For instance, Medicare allocates only one session, which is inadequate for meaningful planning.

Likewise, EOL conversations with family members should take place when an individual is healthy or at the early stages of an illness, diminishing familial pressures and affirming individual autonomy. While early discussions may carry coercive aspects—families often strive for life preservation—prioritizing the patient’s perspective over family desires is crucial.

M. Bennet Broner is a medical ethicist.