The threat isn’t that AI possesses excessive power; it’s that we cease to challenge it.

Artificial intelligence in healthcare is frequently termed groundbreaking, able to identify illnesses, foresee deterioration, and automate decisions once made by humans. However, I propose a different perspective, one rooted not in technology but in historical context.

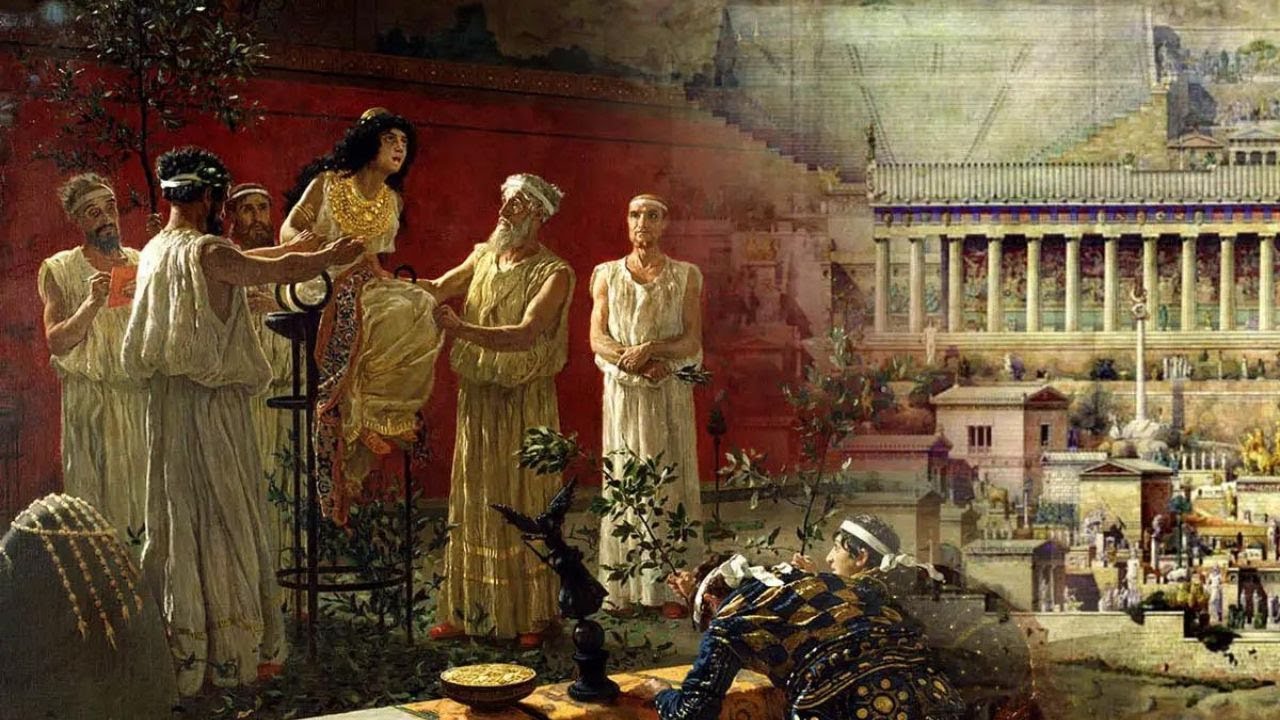

Let us revisit ancient Greece.

There, leaders consulted the Oracle of Delphi not for conclusive answers, but for approval. They confronted uncertainty and sought guidance from a supreme authority. The Oracle provided this. Yet, her messages were vague, influenced by middlemen, and susceptible to misinterpretation.

Does this resonate?

Healthcare’s contemporary Oracle

At present, AI serves a remarkably similar purpose in our medical environment. Whether it’s a predictive model in the emergency department or a significant language model synthesizing records, we increasingly turn to machines for elucidation amidst complexity.

However, there’s a caveat: Both the Oracle and current AI possess five perilous traits:

- Opacity: We frequently lack complete understanding of the decision-making process.

- Bias: Both are influenced by human-derived data, culture, and assumptions.

- Interpretation risk: Outcomes depend on the human interpreting them.

- Self-fulfilling outcomes: Predictions impact behavior, reinforcing the initial forecast.

- Authority creep: The more we trust the tool, the higher the risk of diminishing our clinical judgment.

The black box within the examination room

The allure of AI often stems from its enigma. It can analyze vast amounts of data and identify patterns we might overlook. Yet, as practitioners, we must bear in mind: Insight lacking explainability is not true wisdom.

When a black-box algorithm suggests a treatment or, worse, denies a claim without clarity, we must inquire: On what grounds? Was the training data adequately diverse? Does the model apply to my patient demographic? Are the metrics clinically pertinent?

If we are unable to address those questions, should we be making decisions based on the output?

Bias serves as a reflection, not merely an error.

Similar to the Oracle, whose statements were filtered through priests with personal agendas, AI mirrors our own biases. We input historical data, and it reliably reproduces historical inequalities.

Algorithms might underdiagnose heart disease in women or strokes in Black patients. Risk prediction tools can exaggerate readmission risks in safety-net hospitals, ultimately affecting care delivery. And because these instruments are labeled as “objective,” we may be less inclined to question them, even when we ought to.

When prediction shifts to prescription

AI does not merely predict the future; it has the potential to shape it.

If a sepsis model identifies a patient as high-risk, that patient might receive prompt antibiotics and intensified monitoring. This is beneficial until we begin treating the label rather than the individual. A poorly calibrated model may result in excessive alerts, causing overtreatment. Or even worse, insufficient alerts, leading to delayed care. Yet we continue to adhere to it because the machine indicated so.

This is how AI evolves into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The cognitive toll of outsourcing judgment

Emerging evidence indicates that excessive reliance on AI is associated with declines in critical thinking, particularly among younger clinicians. This phenomenon is termed cognitive offloading: We gradually allow the machine to think on our behalf.

This is advantageous until it becomes detrimental.

When AI makes a mistake (and it will), will we be prepared to confront it? Or will we yield to the algorithm, even when our instincts signal otherwise? This transcends a mere technical concern. It’s a training matter. An ethical dilemma. A human challenge.

Principles for responsible application

As someone who operates at the intersection of medicine and AI, I contend that we can wield these tools judiciously if we remain the ultimate decision-makers. Here’s how:

- Demand clarity: Understand what data informed the model. Inquire who validated it and the population it pertains to. Insist on explainability for clinical outcomes.

- Confront bias: Reflect on how historical disparities might affect predictions. Include varied stakeholders in model creation and implementation.

- Maintain human supervision: Employ AI as a second opinion, instead of a definitive conclusion.