Envision a cancer treatment that circumvents the immune system and targets tumors with enhanced accuracy. The benefits of a cloaked immune system could lead to diminished side effects from therapies and a greater concentration of the medication where it is most necessary. Now picture this potentially safer and highly efficient treatment being accessible on demand. With advancements in genetically altered biologics, it may be nearer than we think.

The research, [featured in Nature Communications](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/41062480/), was spearheaded by Jianzhu Chen and Rizwan Romee from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. The team genetically restructured natural killer (NK) cells to evade the immune system and specifically target lymphoma cells in the bloodstream. These advanced NK cells were equipped with an “invisibility cloak,” paving the way for safer, more robust, “off-the-shelf” immunotherapies. If shown to be safe and effective in humans, this strategy could mark a significant shift in the treatment of hematological cancers.

**CAR-T therapy: An introduction**

The challenge: To comprehend the advancement, revisiting the functioning of CAR-T based therapies and their transformative impact on oncology would be beneficial. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) immunotherapy has demonstrated significant potential in treating B-cell leukemia, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma. Since 2017, multiple CAR-T therapies have gained FDA approval for addressing these liquid tumors. However, their success entails a downside, with 70-90 percent of patients encountering an overactive immune response to the medication, known as a cytokine storm. Ultimately, approximately 3-6 percent of patients may succumb to the drug’s side effects rather than the malignancy itself. Nonetheless, patients with B-cell lymphoma who endure the treatment can anticipate an additional three years of survival, with many leukemia survivors experiencing an extra 5-10 years.

The resolution: CAR-T therapy exemplifies personalized medicine but carries risks, high costs, and requires weeks for production. Researchers extract T cells from a patient with lymphoma, for instance, and alter them to detect specific cancer proteins found in the patient’s tumor. It’s a therapy tailored exclusively for that individual. The modified cells are cultured in a lab for several weeks until they proliferate to a therapeutically effective quantity. Once re-administered into the body, they seek out the cancer and perform their primary function: eradicating it.

**Why CAR-NK could be advantageous**

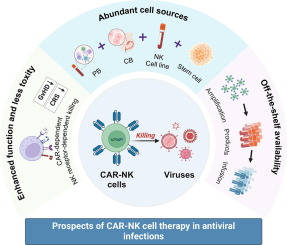

In contrast to T cells, natural killer (NK) cells are part of the innate immune response, and genetically modified versions are less likely to be identified and rejected by the body. They present fewer foreign markers on their surface. Currently, there are multiple first-generation CAR-NK therapies under evaluation in clinical trials, although none have received FDA approval yet.

Similar to the CAR-T approach, they necessitate weeks of cultivation between extraction and re-administration, creating a potentially critical delay. The objective of the New England group was to eliminate the immune recognition markers from NK cells derived from a healthy donor and to track the behavior of these foreign cells once infused into the recipient. If accepted by the host’s immune system, this approach would eliminate the weeks-long culturing phase of the cells. Dr. Jianzhu Chen from MIT remarked: “This enables us to conduct one-step engineering of CAR-NK cells that can bypass rejection by host T cells and other immune cells. Additionally, they are more effective at killing cancer cells and are safer.”

**How to modify an NK cell**

The team’s method followed the trajectory of existing immunotherapies, with two significant enhancements to the cells. Consistent with earlier CAR-T and CAR-NK treatments, the cells were genetically optimized by incorporating an antibody gene fragment that recognizes the tumor-dominant CD19 protein.

Two novel immunity-related modifications were added alongside the tumor recognition protein.

The researchers introduced a small inhibitory RNA molecule aimed at suppressing or “knocking down” the surface proteins on the donor NK cells. These are the external markers that the patient’s immune system might identify as foreign and eliminate before the treatment can take effect.

A gene coding for a checkpoint inhibitor was incorporated. Checkpoint inhibitors reduce the immune response and prevent the rejection of the cell. In the study, the authors employed two distinct genes encoding checkpoint inhibitors, PD-L1 and SCE, to evaluate whether one would be superior to the other. PD-L1 serves as a “don’t attack me, I’m friendly” marker on the modified cells. Conversely, SCE functions by sending a more subtle “nothing to see here, move along” signal to the immune system sentinels.

**Promising results in mice**

To validate their concept, Chen and Romee utilized a mouse model. The team inserted the therapeutic cassette into genetically modified mice that housed a humanized immune system. Furthermore, the mice were injected with active lymphoma cells.