Integrating Emerging Priorities into Medical Education: A Delicate Balance

By M. Bennet Broner, Medical Ethicist

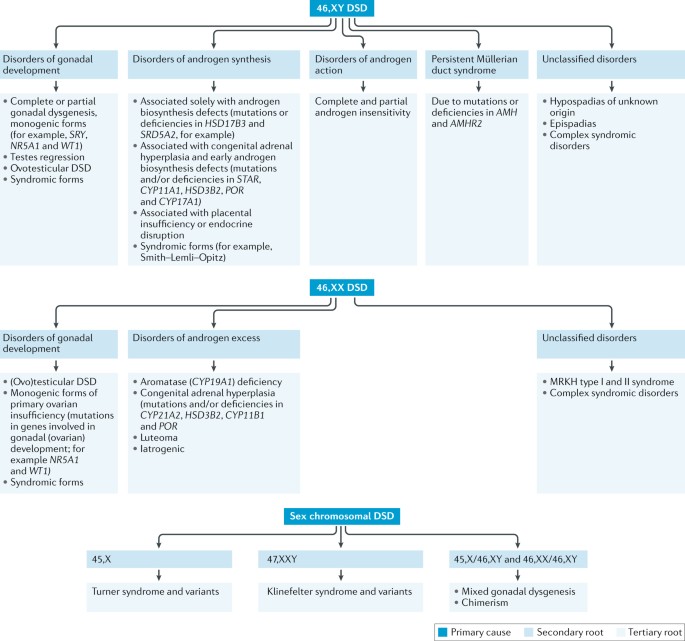

Medical education is often seen as one of the most rigorous and time-consuming training regimens in any profession. In the United States, future doctors undergo four or more years of undergraduate education, followed by four years of medical school, and an additional three to seven years in residency before they can practice independently. Despite this comprehensive training, there is a persistent demand to enrich medical programs with vital yet insufficiently addressed topics such as nutrition, geriatrics, care for non-cisgender individuals, cultural proficiency, and shared decision-making.

Although the rationale behind these demands is commendable and frequently supported by evidence, they pose intricate challenges: How can an already extensive and tightly packed curriculum accommodate additional instructional material? Should these emerging priorities complement or replace existing subjects? Is there potential for better amalgamation outside the classroom, during clinical training, or even after the completion of medical school?

The Constraints of Expansion

Medical curricula in developed nations, especially in the U.S., already rank among the longest available. Introducing new topics risks overwhelming students and diluting essential biomedical content. Consequently, a zero-sum approach may be necessary—new material must displace older or less crucial topics.

If substitution is deemed necessary, what elements should be eliminated? Few would advocate for diminishing courses in anatomy, physiology, pathology, or pharmacology—all of which are fundamental sciences in medicine. Some propose transferring non-clinical lecture hours, like comprehensive biochemistry, into pre-med coursework or online modules. Others suggest reducing certain procedural skills that modern physicians rarely utilize due to specialist referrals.

Alternatively, these newly prioritized topics may not need traditional lecture formats and could instead be woven into ongoing clinical education. Skills in communication, empathy, cultural respect, and treatment for diverse populations are arguably best imparted in interactive, patient-centered environments, guided by experienced and introspective clinicians. Indeed, studies indicate that behavioral skills are acquired more effectively through real-life examples and contexts rather than through formal teaching.

Tailoring Content for Specialties

A key consideration is the relevance of topics to specific specialties. For example, nutrition is vital for internists, family practitioners, endocrinologists, and cardiologists who treat chronic diseases where diet plays a central role. Conversely, subspecialists or proceduralists, like orthopedists or radiologists, may find a deep understanding of nutrition to be of limited practical benefit. Instead of adopting a uniform strategy, specialty-focused elective paths or fourth-year modules could empower students to explore areas that are essential for their prospective careers.

Similarly, geriatrics is critical for any specialty dealing with older populations—internal medicine, psychiatry, neurology, and even general surgery. In contrast, LGBTQ+ care and cultural competence are universally important, as all physicians must provide care to patients from increasingly varied backgrounds with understanding, sensitivity, and respect. These topics may deserve wider, more integrated curriculum inclusion.

The Importance of Clinical Exposure for Non-Scientific Skills

Instructing on skills such as communication, empathy, and cultural sensitivity through traditional lectures has inherent limitations. These competencies are best developed through iterative, experiential learning. Contextual experiences—observing a clinician converse with a grieving family, or addressing vaccine skepticism with a concerned parent—foster true understanding of respectful patient care. The demonstration of empathy by educators, combined with reflective dialogue, is crucial in establishing these behaviors as both professional and therapeutic necessities.

Adapting to the Realities of Medical Practice

Nonetheless, it is essential to ensure that any educational enhancements align with the realities of contemporary practice. Many physicians operate under time constraints, expected to manage a growing patient load each hour. This pressure, fueled by reduced reimbursements and administrative demands, restricts doctors’ abilities to connect deeply with each patient. Therefore, the aims for meaningful, patient-centered communication must be reconciled with institutional and systemic limitations—a tension that reforms in education alone cannot resolve.

Furthermore, the responsibility for the quality of the patient-provider relationship cannot rest solely on physicians. While shared decision-making is considered the ideal, it necessitates commitment and participation from both medical providers and patients. However, as experience indicates, many patients either wish for physicians to make choices for them or lack the readiness—due to motivation deficits, illiteracy, or previous trauma—to comprehend or act on medical advice.

Take, for instance, young women attending health education sessions in a high-risk obstetrics clinic. Despite clear and accessible presentations of life-saving information, many appeared disengaged, even resistant to the content. Their reactions reveal a gap that education alone cannot bridge. It is overly simplistic to hold physicians accountable for patients’ medical decisions when those choices neglect available resources and guidance.

Motivation and Accountability in the Age of Information

It is no longer valid to claim that patients do not have access to trustworthy health information. With approximately 96 percent of adults online, and public access provided through libraries and clinics,