As an infectious disease fellow years ago, I was summoned to the hospital in the early hours of the morning for a potential measles case. I reviewed the clinical essentials, as I was not entirely certain what to anticipate, having not encountered a measles case previously. The emergency room staff had swiftly isolated the patient in a negative pressure room. I donned a mask and entered to examine the patient, a teenager from abroad who was visiting with a school group.

He exhibited all the indicators of measles: a rash that began on his face and extended down his body, fever, conjunctivitis, coryza, and a cough (the “3 C’s”), and most astonishingly (to me, at least), Koplik spots. During this time in the 1990s, I had witnessed many oral cavity abnormalities, predominantly oral thrush and oral hairy leukoplakia in HIV/AIDS patients. The Koplik spots were unmistakable and corresponded precisely with my readings: tiny grains of gray-colored sand, or salt, surrounded by an erythematous base on the buccal mucosa. In that moment, I knew, as the nurses likely had, that this patient indeed had measles.

We promptly contacted the local health department, which offered expert advice and outlined the next steps. My attending physician arrived and evaluated the patient. Before dawn, the patient and his group were en route home (by private vehicle), and a local measles outbreak was prevented.

So, why is this pertinent today? Unfortunately, we find ourselves in an extraordinary scenario in the U.S. this year. There has been a significant number of measles cases, exceeding 1000 as of late May 2025, reported across 31 states, along with three measles-related fatalities. Two of these deaths occurred in children, marking the first pediatric measles deaths in the U.S. in 22 years. Furthermore, numerous falsehoods regarding measles and the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine have been circulating. This creates a tragic mix.

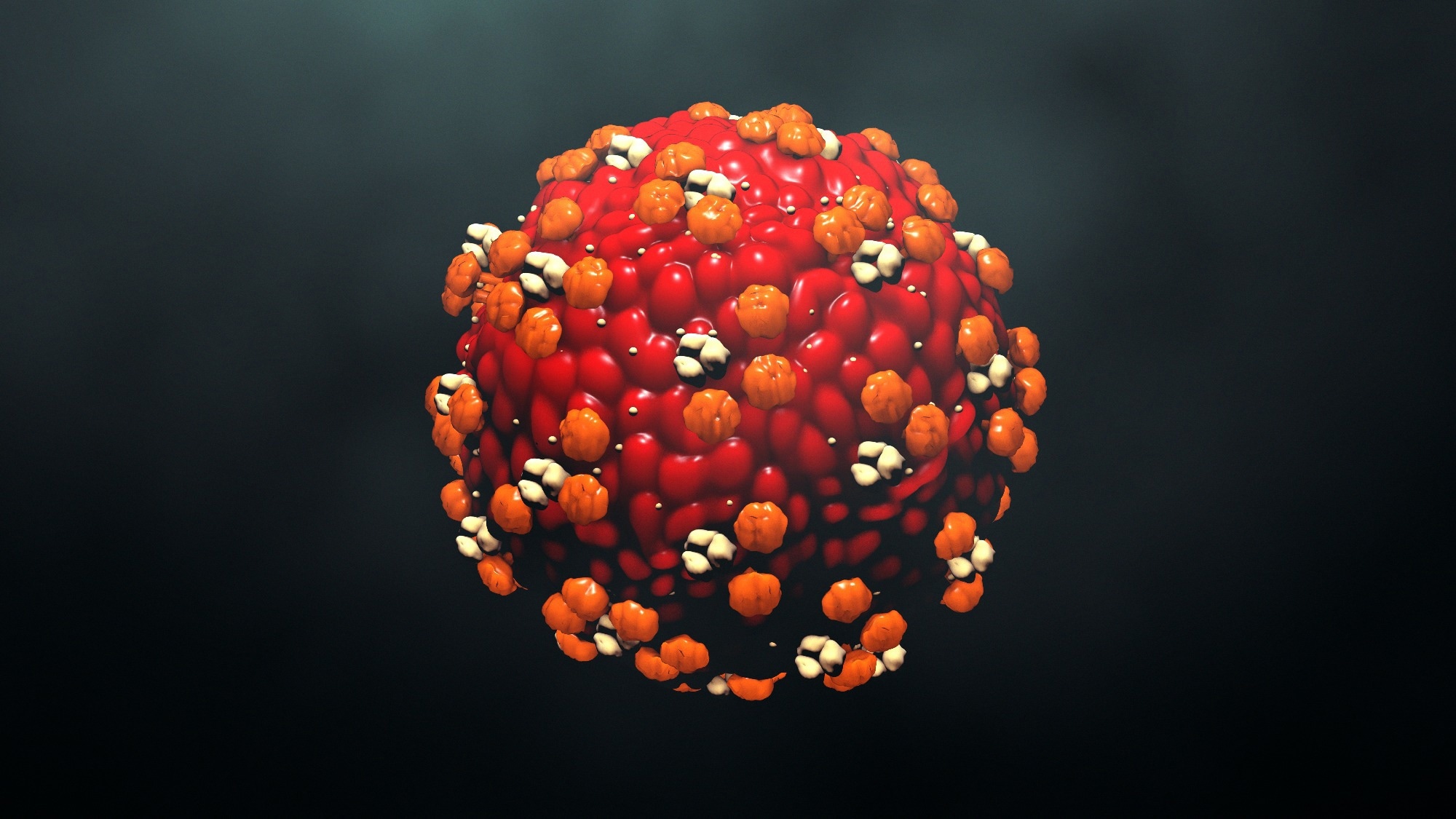

MMR vaccination rates among kindergartners have been declining, more sharply since the COVID-19 pandemic. A vaccination coverage of 95 percent is necessary to establish herd immunity and curb the spread of measles. In certain areas across the nation, rates have plummeted below this threshold. Measles is among the most contagious respiratory illnesses, infecting 9 out of 10 susceptible individuals who come into contact with it. Moreover, the virus remains airborne. Susceptible individuals may be at risk if they enter the same room where a measles patient had been just two hours prior.

Why does this matter? Measles can lead to severe complications, including death in roughly 1 to 3 per 1000 cases. Before the vaccine was introduced in 1963, the U.S. experienced three to four million measles cases annually, leading to 48,000 hospital admissions, 1000 instances of chronic disability, and 400-500 deaths. A more effective vaccine was made available in 1968 and is still in use today. Following its introduction, measles rates in the U.S. dramatically decreased, resulting in the disease being declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000.

The sole means of preventing measles is through vaccination. Two doses of the MMR vaccine are 97 percent effective at warding off measles and provide lifelong immunity. The MMR vaccine has been administered to millions of children globally and is estimated to have saved 60 million lives worldwide since 2000. Being a live attenuated vaccine, it should not be administered to patients with weakened immune systems or pregnant women. It does not “kill people every year” nor does it induce blindness, deafness, or autism. The vaccine may cause a temporary rash or fever, and it can trigger a febrile seizure (~1 in 3000 doses, with an elevated risk for those with a personal or family seizure history).

Steroids, cod liver oil, and antibiotics do not prevent or treat measles. Following a measles diagnosis, two doses of vitamin A are recommended, based on evidence indicating benefits for children with vitamin A deficiencies. Regrettably, there have been instances of children presenting with vitamin A toxicity, clearly stemming from well-meaning but misinformed parents.

What are some other complications associated with measles? In medical school, we all learned about the dreaded subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (hard to say), a condition that manifests 7–10 years after measles and leads to death. This always seemed particularly tragic to me, as it represents something devastating that appears to emerge from nowhere. Pneumonia is the most frequent cause of hospitalization and death. Other potential complications include diarrhea, otitis media, and deafness. Children may experience acute encephalitis or acute disseminated encephalitis.