John, a gentleman in his early sixties, spent nine months awaiting his appointment to discuss memory issues. When he finally presented, I had a mere twenty minutes. Eighteen of those were dedicated to investigative work, gathering pieces of history from conflicting narratives, reconstructing months of decline from unreliable recollections, and conducting a paper-based subjective memory assessment. What should have been a comprehensive consultation centered on patient care was condensed to just a few rushed minutes at the conclusion. He departed with additional tests scheduled and a follow-up meeting in four months.

This situation is not uncommon. Throughout neurology departments, we are attempting to accommodate chronic, progressive illnesses within a framework designed for more clear-cut presentations. This disparity is not only inefficient; it undermines trust, burdens clinical teams, and squanders resources that healthcare systems cannot afford to lose.

John’s results arrived in a fragmented manner: a scan one week, followed by bloodwork the next. Each step required another review, another letter to his primary care physician, and yet another appointment. In the interim, symptoms fluctuated, family members devised care strategies, and everyone awaited the next brief opportunity to connect.

**The core design flaw**

Contemporary health systems are constructed to excel in acute care scenarios. Protocols for heart attacks or strokes are crafted for optimal efficiency, as time is critical for positive outcomes. Surgical pathways are refined to ensure patients reach the operating room when urgently needed. Emergency departments triage swiftly to facilitate patient flow through the system. These successes adhere to a straightforward formula: a clearly defined problem, a targeted intervention, and a quantifiable outcome. If all proceeds as planned, the case is resolved.

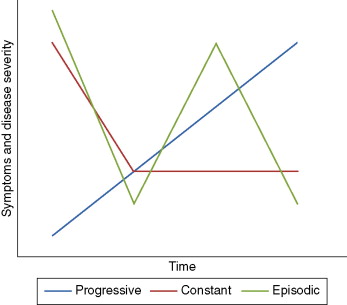

Unfortunately, care for Parkinson’s and dementia does not conform to this model. These conditions progress over months and years, not merely days. Symptoms can vary from hour to hour in ways that patients may not reliably remember months later. They exhibit numerous overlapping symptoms that interact in complex, unpredictable ways. These diseases do not resolve; they merely advance.

I frequently encounter Parkinson’s patients who have lived with the condition for many years struggling to remember whether a medication was effective one month but detrimental another, or if their tremor has improved while their sleep has worsened. Decisions regarding medication adjustments—ones that alter brain chemistry and may yield significant side effects—are made based on these fragmented memories. Six to twelve months later, this cycle is repeated.

The system presumes that we can distill two decades of disease management from twenty-minute encounters held twice a year. It is akin to attempting to grasp the plot of a feature-length film by only catching a few minutes at the start and mid-point, yet still being expected to provide a thoughtful critique of the narrative and character depictions.

**The cascade of inefficiencies**

This disconnect generates inefficiencies that reverberate throughout the system. For John, ambiguity during that initial visit precipitated additional appointments to clarify the diagnosis. The resulting delays translated into months without treatment and support, adversely affecting his quality of life.

In the case of Parkinson’s, once diagnosed, the cycle ultimately recurs: trial-and-error medication modifications grounded in the best assessments that can be derived from subjective recollection, negative side effects or acute incidents leading to emergency visits, and further consultations for assistance. Between visits, symptoms fluctuate without guidance. Families initiate urgent calls. Emails are sent with further inquiries. Results arrive weeks later, each necessitating review.

These fragments also demand substantial administrative time. Primary care physicians, who might manage routine adjustments if they had better access to information, instead redirect referrals back to specialists. Everyone operates with partial visibility, fragmented efforts, duplicating work, and missing opportunities for early intervention.

**We have addressed this challenge before; just not in this arena.**

Endocrinology confronted a similar obstacle decades past. Diabetes patients traversed crises until remote glucose monitoring facilitated daily oversight, early intervention, and diminished hospitalizations. Continuous glucose monitoring further revolutionized their care, offering teams real-time insights and enabling patients to modify their daily routines accordingly.

Continuous data liberated clinical teams from investigative work, allowing them to concentrate on timely, precisely aimed treatment. Neurology possesses the same potential. We can now objectively assess tremors, vocal alterations, gait patterns, and cognitive function using tools that patients already possess. Entire care teams can share this data, replacing speculation with clear trends. The technology already exists; it merely hasn’t been integrated into the existing model.

**What must evolve**

Firstly, make symptoms visible between visits. Presently, crucial decisions hinge on in-clinic snapshots. Parkinson’s alone may encompass dozens of distinct motor and non-motor symptoms, each evolving daily. In the absence of objective, continuous tracking, care devolves into guesswork. Ongoing measurement would enable clinicians to observe patient progress over time, adjust earlier, and avert preventable crises.

Secondly, unify the complete care team. Care should not terminate at the neurologist’s office. Nurses, therapists, pharmacists, and primary care physicians all have significant roles, but they often function in isolation. Shared, objective information and clear protocols would empower each member to contribute substantively, alleviating the burden on limited specialists.

Thirdly, patients and caregivers ought to be engaged as active collaborators. Many are already monitoring symptoms and modifying routines.