During one of my internships as a junior, I encountered a patient whose care tested my cultural understanding rather than my medical expertise. Mr. L., a 20-year-old university student from China, came to the clinic reporting low back pain. He was convinced that his discomfort stemmed from an “improper” posture. While trying to clarify this belief during our conversation, I faced strong opposition. After a more in-depth discussion with my supervisor, I understood that his resistance wasn’t rooted in distrust toward medical advice. Rather, it derived from formative experiences where his parents frequently reprimanded him for his posture. At our follow-up appointment, he shared that in his culture, parental views and decisions are rarely questioned. This experience underscored the fact that patients’ beliefs and behaviors are shaped by their cultural contexts; hence, intercultural competence should be a fundamental skill for clinicians.

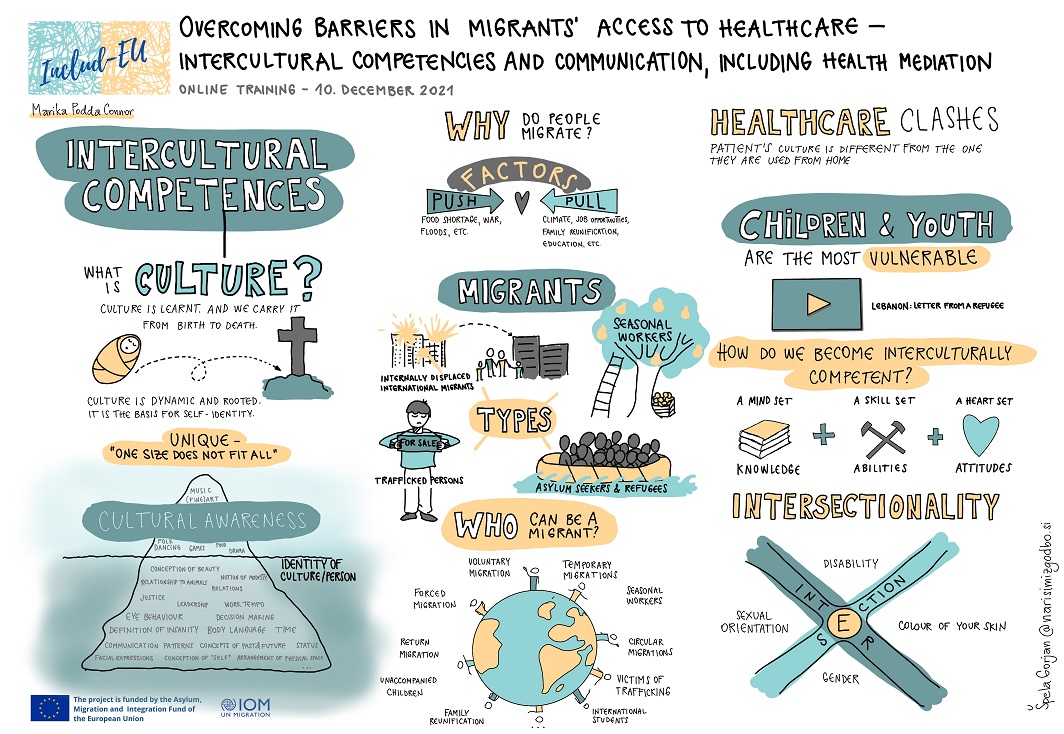

Before delving into intercultural competence, it is important to clarify what culture entails. Research indicates that “Culture is a collection of guidelines (both explicit and implicit) that individuals adopt as members of a specific society, which informs how they perceive the world, feel about it emotionally, and interact with others.” This definition emphasizes that culture is associated with a group or society, is learned throughout one’s life, and spans various dimensions, from the more apparent to the subtler aspects.

Intercultural competence extends beyond mere cultural awareness. “Intercultural competence refers to the capacity to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural contexts based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes.” Such relational skills have always been essential for health care professionals, and enhancing intercultural sensitivity enables these professionals to utilize these skills more effectively when treating patients from a variety of cultural backgrounds. In the context of health care, “cultural competence involves a continuous process where the healthcare provider endeavors to work effectively within the cultural framework of the client (individual, family, community).” Campinha-Bacote’s model presents cultural competence as a fluid process that includes Awareness, Skill, Knowledge, Encounters, and Desire (ASKED). To deliver care that is respectful and effective across different cultural boundaries, clinicians must develop self-awareness, work diligently to enhance their clinical abilities, gather cultural knowledge, and possess the desire and motivation to engage with diverse cultures.

The cultivation of intercultural competence is crucial for enhancing the overall efficacy of health care and the dynamics between providers and patients. Globalization has led to an increase in population diversity. Furthermore, it serves as a significant impetus for fostering intercultural sensitivity among health care providers. Research from 2018 indicated that international migrants made up over 10 percent of the population in multiple European countries. International migration trends continue to increase globally, with international migrants representing around 14 percent of the European population by 2024. A core principle for any progressive society is ensuring equitable access to health care for all societal members, including geographical, religious, sexual, and gender minorities.

As diversity grows, so does the requirement for clinicians to communicate effectively across cultural boundaries. Health care professionals lacking cultural competence may face communication obstacles that can severely diminish the quality and effectiveness of care. For instance, according to Edward T. Hall’s theory, cultures can be categorized into “high context,” which relies significantly on indirect communication, assumptions, and non-verbal signals, and “low context,” which emphasizes explicit and direct expression. If a clinician overlooks these cultural traits, they risk fostering misunderstandings and disengagement from the patient. Edwin Hoffman’s TOPOI model outlines the levels of communication where “noise” (communication differences) can occur. These levels encompass language (both verbal and non-verbal), the organization of logic and values, relational roles, organizational structures, and underlying intentions or needs. If cultural distinctions in context, space, time, language, relational expectations, or organizational norms are not acknowledged and addressed, they can present notable barriers between health care providers and patients. Fundamentally, intercultural competence lays the groundwork for a safe atmosphere where patients can communicate freely and be genuinely understood.

The journey towards developing intercultural competence is not a straightforward process dictated by a set of guidelines, but rather a path that initiates with self-awareness. Health care providers must begin by examining and comprehending their own cultural influences. Past experiences, social settings, and upbringing shape how we communicate and perceive the actions of others. Clinicians aiming for intercultural competence should critically evaluate these influences and recognize how they inform their social interactions. After becoming aware of their own cultural backgrounds, they also must acknowledge that differences exist. These differences may surface in communication styles, values, or social expectations and may at times contradict their own beliefs. Consequently, prejudices may arise. Nonetheless, an interculturally competent health care provider can identify these biases and prevent them from obstructing care.

After clinicians establish self-awareness,