The deficiency of physicians in the United States represents a pressing and significant concern. Forecasts from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) predict that by 2034, the country might experience a shortage ranging from 37,800 to 124,000 physicians. Primary care will be disproportionately impacted, with an anticipated lack of up to 48,000 doctors. Rural and underprivileged communities are likely to endure the greatest challenges.

This shortfall arises from various factors, primarily the Medicare Graduate Medical Education (GME) funding freeze established in 1996, which significantly limits financial backing for new residency positions. While several states have made notable investments to expand residency opportunities, especially in primary care fields, these initiatives have yet to fulfill the expected national demand for physicians.

Evolution of practice

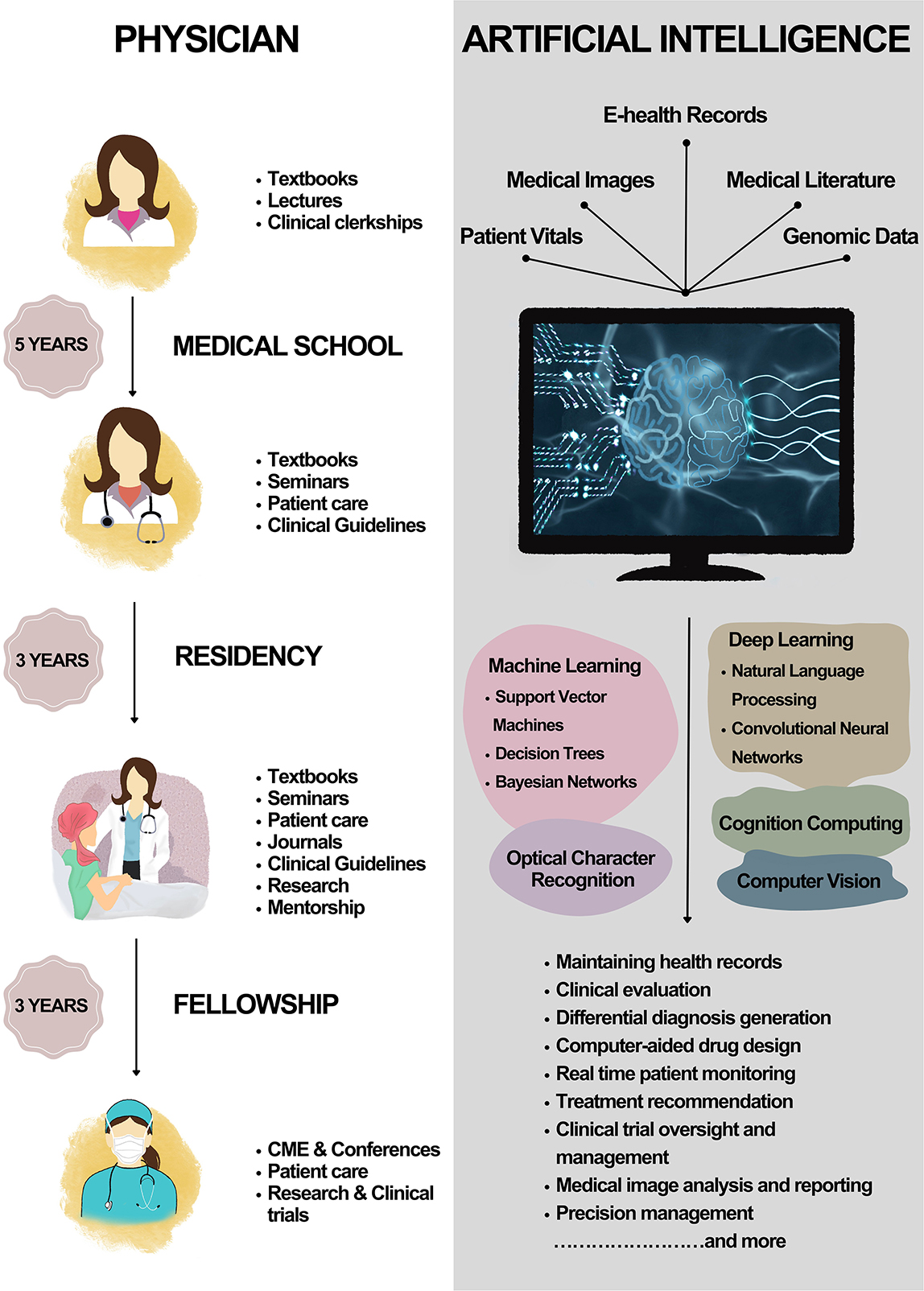

Artificial intelligence (AI) provides promising resources to enhance the efficiency and reach of our existing physician workforce. AI has already demonstrated substantial efficiency improvements in automating administrative functions, optimizing staffing and resource distribution, assisting with remote monitoring and virtual care, and streamlining patient flow and discharge workflows. These innovations do not replace physicians; instead, they modify their roles. By managing routine responsibilities, AI can allow doctors to oversee larger patient groups and concentrate on intricate care that necessitates human insight.

As AI integration progresses, physicians will increasingly oversee AI-enhanced care systems instead of executing every task independently. This transition necessitates a reevaluation of what “workforce shortage” signifies—not simply how many physicians are needed but also how to effectively utilize their skills within technology-augmented healthcare frameworks.

Medical education must equip physicians for this transformed landscape. Clinicians must be proficient in AI to assess and implement these technologies responsibly. Some institutions are beginning to adapt, such as Harvard Medical School, which has launched a month-long introductory course on AI in healthcare for its Health Sciences and Technology track, highlighting both the advantages and limitations of AI in clinical settings. Other schools, like Long School of Medicine, have initiated a dual degree program, MD/MSAI (Master of Science in Artificial Intelligence).

Equity concerns

Nevertheless, the national landscape diverges from the local realities. While AI has the potential to enhance overall care efficiency, it will not bridge every divide. Rural regions and primary care environments may continue to encounter access challenges, particularly where broadband, staffing, or infrastructure are inadequate. We must consider two perspectives simultaneously: How can AI alleviate the overall pressure on the physician workforce while also addressing ongoing local deficiencies?

Moreover, many tools are built for large hospital systems with advanced electronic medical records, which may inadvertently marginalize smaller practices and rural clinics. AI models developed using data from extensive systems might also struggle in varied care environments. To avoid exacerbating health care inequities, it is essential to ensure that FDA oversight assesses AI performance across diverse contexts and guarantees that AI solutions are suitable for all types of practices.

Moving forward

The physician shortage is projected to intensify. We need to reassess our beliefs about how to tackle it. As healthcare delivery transforms, crucial questions arise:

What type of workforce do we genuinely require?

Where are the most pressing gaps?

How can public funding facilitate both training and smarter, AI-enhanced systems?

The most critical shortage may not be of physicians but rather a lack of foresight in reimagining healthcare delivery for a new age.

Amelia Mercado is a medical student.