We are perpetually reminded of the scarcity of organs and the individuals who have lost their lives waiting for a kidney. Much like fish that don’t recognize the water they swim in, we have come to accept the escalating tide of kidney failure as something natural and inevitable—yet it is not. The most pressing question remains unasked: Why do so many kidneys fail?

Diabetes leads as the primary cause of kidney failure, with 40 percent of those on the kidney transplant list being diabetic. Every day, 170 diabetic patients in the United States start dialysis or receive a kidney transplant; that equates to 62,000 individuals per year.

Medicare allocates an astounding $50 billion each year on dialysis and transplantation through the Medicare End Stage Renal Disease Program (1972). Despite only 1 percent of Medicare patients experiencing kidney failure, their treatment constitutes 7 percent of the Medicare budget.

The prevalence of diabetes is rapidly escalating. Presently, 34 million adults in the U.S. have diabetes, a figure expected to rise to nearly 55 million by 2030. More than one third will develop diabetic kidney disease, contributing to new kidney failure cases and increased Medicare spending for dialysis and transplantation.

The anticipated annual expenditure for diabetes and its comorbidities by 2030? An unsustainable $622 billion, reflecting a 53 percent increase since 2015. This is not a future dilemma. It is occurring right now.

Medicaid: the primary line of defense

According to the Americans with Disabilities Act, diabetes is acknowledged as a disabling condition. When prevention and early intervention are overlooked, young individuals face years of illness and complications—including kidney failure, heart disease, visual impairment, amputation, and chronic pain. Eventually, we all shoulder the substantial costs of managing kidney failure.

One in six Americans—15.8 percent—are diabetic. Medicaid is crucial for prevention and treatment, covering 72 million citizens—including 20 percent of U.S. adults and 40 percent of minors. Nonetheless, many struggle to afford necessary care. In 2021, the CDC reported that 16 percent of insulin users rationed their supply due to costs, placing them at risk for severe complications—including kidney failure.

Cuts to Medicaid will diminish access to early diabetes screening and treatment, prompting increased insulin rationing, uncontrolled diabetes, and ultimately, more kidney failure.

Diabetes: a preventable condition profoundly influenced by social factors

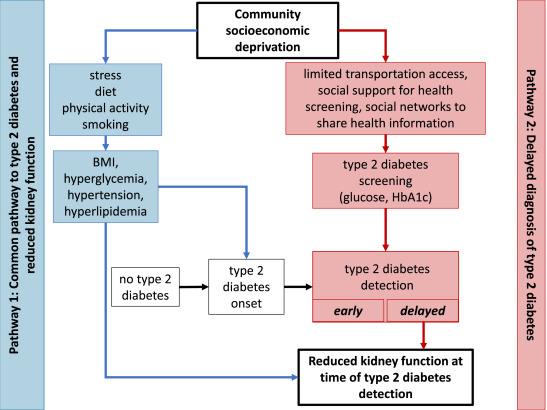

Type 2 diabetes constitutes 90–95 percent of all diabetes, a preventable condition influenced by social determinants: inadequate health insurance, toxic stress, food insecurity, lead exposure, and pollution. These challenges are significantly shaped by both race and socioeconomic status, commencing in young adulthood.

Individuals from minority communities—Asian, Hispanic, Native, and Black Americans—are 1.5 to 3 times more susceptible to developing kidney failure. Nearly 60 percent of those awaiting a kidney come from minority backgrounds. A diagnosis by age 40—known as early-onset diabetes—triples the risk of kidney failure compared to those diagnosed later.

This crisis is already intensifying. When the COVID-19-era protections against Medicaid disenrollment lapsed in March 2023, around 20 million individuals lost health coverage.

The unintended effect of reducing Medicaid will be to transfer costs to the Medicare End Stage Renal Disease Program (1972) as more patients with inadequately managed diabetes develop kidney failure, increasing our reliance on organ transplantation, which now incorporates the use of genetically altered pig organs. This trajectory reflects a significant policy failure: we have opted to finance the aftermath of disease while disregarding preventive measures upfront.

It also poses urgent ethical considerations about our care (or lack thereof) for young people with diabetes, our treatment of sentient beings, and the societal risks we are willing to accept. The use of pig organs for transplantation could present a route for zoonotic infections, creating public health threats that extend well beyond individual patients.

Transplantation is a treatment, (not a remedy)

The initial six-month cost of a kidney transplant is $446,800. Complications can include cancer, infections, cardiovascular issues, and new onset diabetes following transplantation (NODAT). Psychological issues, such as depression, PTSD, and suicidal thoughts, are prevalent.

Results for diabetic transplant recipients are frequently subpar. Failed transplants—a common and unfortunate occurrence—are the fourth leading cause of initiating dialysis; they embody a costly systemic failure, resulting in $1.38 billion annually. Currently, 14 percent of those on the waiting list are for a second or third transplant.

Policy decisions

The Indian Health Service successfully reduced kidney failure by 54 percent through the integration of diabetes and kidney care in community clinics. This achievement can and should be duplicated on a national scale.

By concentrating so intently on transplantation, have we reframed the diabetes epidemic as a crisis of organ scarcity, highlighting the feared complication of kidney failure while neglecting its root causes?

We are overwhelmed by a spike in preventable diabetes-related complications and the soaring expenses of the Medicare End Stage Renal Disease Program. We cannot afford to rely solely on transplantation as a solution for this expanding crisis.