**The Quiet Devastation of Pancreatic Cancer on Black Achievement**

The names sound like a tribute to Black achievement: congressman John Lewis, the civil rights legend who crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge and helped transform America; congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, the relentless champion for justice who served Houston for nearly thirty years; Aretha Franklin, the Queen of Soul whose voice shaped generations; reverend Dr. Calvin O. Butts III, the prophetic voice from Abyssinian Baptist Church who tirelessly advocated for his community; and most recently, D’Angelo, the R&B innovator whose artistry reshaped modern music.

All succumbed to pancreatic cancer, and all are part of a heartbreaking trend that the healthcare system continues to overlook. Pancreatic cancer is a universal killer with deeply uneven effects. Research from the Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) program has shown that monitoring high-risk individuals can uncover pancreatic cancer at earlier stages. Patients diagnosed via screening programs boast a median survival rate exceeding five years compared to merely eight months in the general population. Even more striking, 50 percent of high-risk patients who were screened survived five years, contrasting with only 9 percent of those diagnosed through standard care.

Let that resonate. We’re discussing a fivefold increase in five-year survival. We’re considering the distinction between mourning someone months after diagnosis and witnessing them enjoy their grandchildren growing up. Yet, when I review present screening recommendations, I don’t find specific, actionable advice for African Americans, despite our community’s disproportionate struggle with this illness.

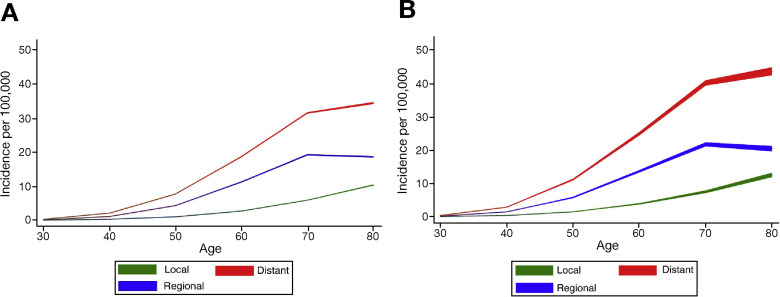

Black Americans experience higher pancreatic cancer incidence rates than white Americans. We tend to be diagnosed at younger ages. Our outcomes are worse. And when Representative John Lewis was diagnosed in December 2019, or when Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee revealed her diagnosis in June 2024, or when Aretha Franklin confronted the disease in her final months, they joined countless African Americans grappling with this diagnosis annually, often far too late for effective treatment.

High-risk individuals under surveillance were significantly more likely to be diagnosed at stage I (38.5 percent) compared to the general population (10.3 percent), and presented with smaller tumors upon diagnosis. This isn’t conceptual. This translates to lives saved through early detection.

The medical community acknowledges that specific populations require monitoring. Current guidelines advocate screening for patients with familial pancreatic cancer, genetic syndromes like BRCA mutations, and particular hereditary conditions. These recommendations exist because we know these groups face increased risk.

But where are the racially specific guidelines? Where is the directive that African Americans, especially those experiencing new-onset diabetes after age 50—which is associated with pancreatic cancer risk—should receive intensified surveillance? Where is the dialogue about community-level screening initiatives in Black neighborhoods where pancreatic cancer prevalence is the highest?

The silence is both loud and lethal. I can already hear the counterarguments from my peers: “We require more studies focusing on African American populations.” “The cost-effectiveness of race-based screening is not established.” “We don’t want to instigate health anxiety or overtesting.”

To that, I ask: How many more John Lewises must we lose? How many more Aretha Franklins? How many more community leaders, mothers, fathers, pastors, teachers, and neighbors must perish while we await the definitive study?

We do not demand such certainty for other screening programs. We don’t hesitate for flawless data before endorsing colonoscopies or mammograms. We make evidence-informed choices that weigh benefits and risks, updating our recommendations as we gain more understanding.

In the case of pancreatic cancer, focused screening has exhibited significant survival advantages, with screened patients living an average of 4.5 years longer than those diagnosed through standard care. If we possess tools that are this effective for high-risk populations, and we recognize that African Americans face elevated risk, why are we not proactively pursuing screening pathways for this demographic?

I’m not suggesting CT scans for every Black individual in America. I’m advocating for a sensible, risk-based approach that acknowledges racial disparities as a significant risk factor deserving clinical focus.

Current screening protocols for high-risk individuals utilize MRI and endoscopic ultrasound, typically conducted annually or alternating between the two methods. These are established, safe procedures available at leading medical institutions.

Here’s what a race-conscious screening protocol might encompass:

– **Tier 1 – enhanced surveillance:** African Americans with any of the following should be offered annual pancreatic cancer screening starting at age 50 (or earlier if additional risk factors are present):

– New-onset diabetes after age 50

– Family history of pancreatic cancer

– Known genetic mutations (BRCA1/2, Lynch syndrome, etc.)

– Chronic pancreatitis

– Tobacco use in conjunction with any other risk factor

– **Tier 2 – risk assessment:** All African American adults should undergo pancreatic cancer risk assessment at age 50, along with education regarding symptoms, risk factors, and the necessity of prompt evaluation.